He Spent 11 Years Proving to the Russian State That He's Alive

Four personal stories of Russians who were stated dead by the government — by mistake — and fought back for their lives.

Russia can be one hell of a Kafkaesque bureaucratic labyrinth — each year, dozens of citizens are stated dead — by mistake. I collected the personal stories of four people as they fought back against a system that has stripped them of their identities, rights, and dignities.

On the morning of July 3, 2004, retired fire service warrant officer Vladimir Gusev learned that he had died two and a half years ago.

A native of the small mining town of Kopeysk in the Ural Mountains, Vladimir Nikolaevich had led an exciting life. Born on January 17, 1956, to a miner and a dentist, he graduated from the Chelyabinsk Automotive Transport Technical School, served in the army, worked eleven years at a defense plant, and spent four years driving heavy trucks hauling coal. He took a loan from a bank, built a house, got married, raised two daughters, and traveled to Tashkent and Seydi in Turkmenistan. In 1993, he joined the fire department, responding to emergency calls as part of the duty crew.

At 48, Gusev retired with a military pension and decided to take a break. He bought a new silver VAZ-2111 car – “the color of an aluminum pot,” his daughters joked. He went to the police to register his car, waited in line, handed in his documents, and stepped aside to wait. Ten minutes later, Gusev was called back and, after his documents were returned, was told that they couldn't register the car: “It's not possible because you can't register cars for corpses.”

Gusev felt the noisy crowd staring as he awkwardly asked, "What should I do?" The widow replied, "I have no idea," and asked the dead man to bring some proof that he was alive. All Gusev could find out then was the date of his death – December 14, 2002. The cause was unknown.

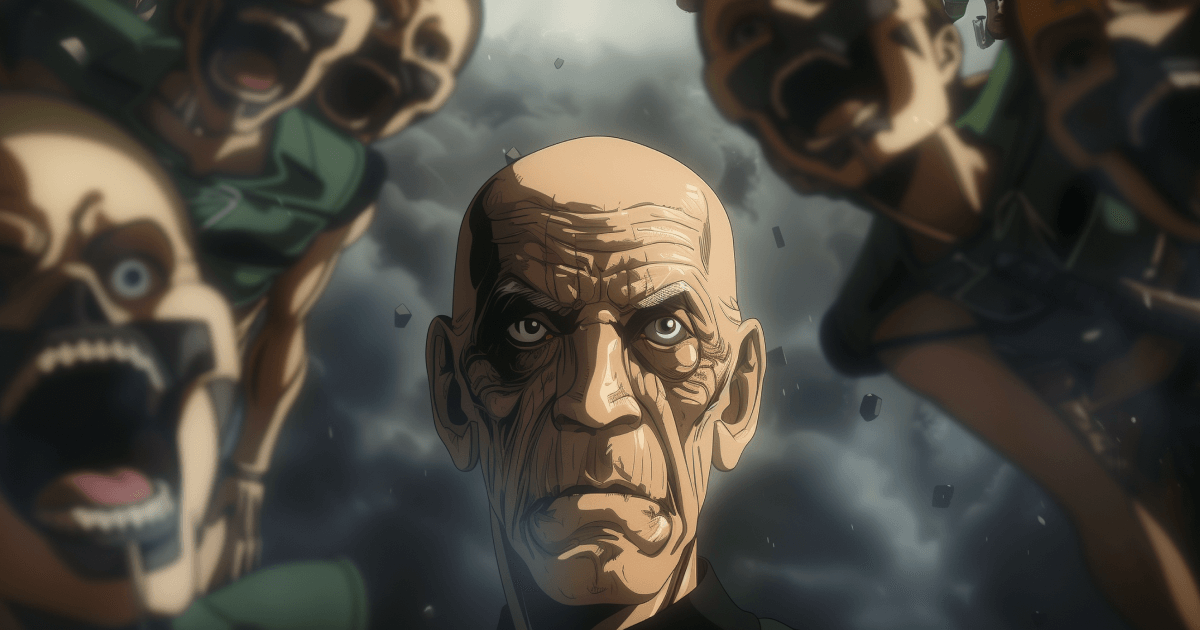

The living Vladimir Gusev is 162 centimeters tall, weighing 58 kilograms, with a bald head and a quiet, slightly shy voice. When the fire crew goes to extinguish fires, he always makes his way to the most inaccessible places, and if there's no ladder, he can climb up on his comrades' backs. Even though he considers himself a temperamental person, he now recalls the story of his death almost without emotion. At first, Gusev thought it was a silly mistake and approached the head of the Kopeysk police. After listening, he instructed his subordinates: the man has a passport and registration, he has a car, and he should be able to drive it, so solve the problem. After that, the silver VAZ was registered, and Gusev thought it was all behind him. But a month later, he needed to transfer to his name an old Moskvich car left after his father's death, and he was refused again: "I couldn't imagine it was so serious. How could this happen to me? It doesn't happen to anyone."

He was wrong.

Here's what happens when a person dies in Russia. The police and ambulance or a local doctor from the clinic confirm the death and issue a death confirmation form and a corpse examination protocol. The body is taken to the morgue. The morgue issues a medical death certificate. Law enforcement, if necessary, identifies the deceased. All these documents are sent to the civil registry office. The civil registry office takes the passport, issues a death certificate, and forms №33 – a death notice. Then, they send the information to the tax and migration services, local administration, military recruitment office, pension fund, and medical and social insurance agencies. After this, the person is removed from all registries – legally, they no longer exist. Sometimes, the wheels of bureaucracy malfunction and a living person is declared dead. Although cases like this occasionally make it to the "odd news of the day" section of the local press, there have been dozens of such stories in the last decade. Novokuznetsk, Kyshtym, Moscow, Kopeysk, Shakhty, Asbestos, Nizhnevartovsk, Mariinsk, Kandalaksha. Together, they form an unofficial census of resurrected Russians.

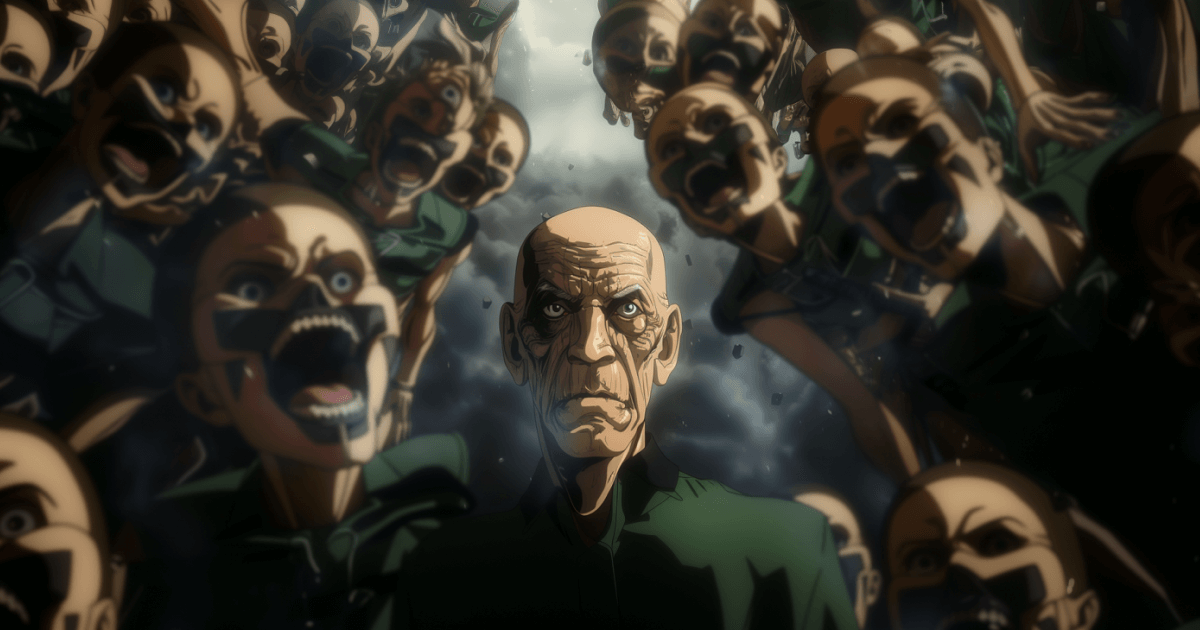

Vladimir Gusev could never have imagined that for the next 11 years, he would prove to the Russian state that he was alive, let alone that he was one of the hundreds of Russians who, due to a bureaucratic error, found themselves in a similar hell, right amid the country of living dead.

I. The death record №393

The bureaucratic mishap and "death" of Vladimir Gusev didn't start so blatantly. In December 2002, in the streets of Kopeysk, police found a frostbitten corpse, later buried under his name. Following standard procedures, the body was sent to the morgue of the regional forensic bureau. There, doctors conducted an autopsy and issued a certificate stating death by hypothermia. As it was a non-violent death, the prosecution didn't initiate a criminal case and passed the papers to the police to identify the deceased. This is where the mystery begins.

Court documents reveal that in January 2003, the head of the criminal search department in Kopeysk sent a letter to the forensic bureau. According to the police, Vladimir Nikolaevich Gusev, born April 27, 1956, was a native of Verkhny Ufaley, Chelyabinsk region. He was a namesake of Vladimir Gusev, born the same year in a neighboring city. How exactly the dead native of Verkhny Ufaley turned into the still-living resident of Kopeysk remains unexplained to this day. The body lay in the morgue for four months before being buried: after receiving all necessary certificates, the local civil registry office created death record №393.

Denis Polezhaev, the deputy prosecutor of Kopeysk, believes the first mistake was made by the police officers who breached the procedure and didn't communicate with the deceased's relatives. However, the police deny their fault. The civil registry office also doesn't admit to any error, stating, "We executed in full what was presented to us." As usual, the registry office sent the data to the relevant departments, but the information didn't reach the tax and pension fund services. "For unknown reasons," believes the deputy prosecutor. Consequently, Vladimir Gusev was only half-legally recognized as dead: his passport remained valid, registration wasn't annulled, pension was paid, and taxes were levied, but he was no longer included in the voter lists.

Gusev describes his quest to find the cause of his death as an epic, which took a year of his life. At the passport office, they sent him to the civil registry, from where he was dismissed. Then he went to the tax service and, from there, to the prosecutor's office. They initially laughed at Vladimir Nikolaevich but eventually found the old case.

The deputy prosecutor explained: too much time had passed, there was no sense in searching for the guilty and "we won't stir this up." Instead, he wrote an official appeal to the civil registry. Gusev cautiously asked: what if it doesn't help? The deputy prosecutor, indignantly replied, "I am the deputy prosecutor! I will demand answers from them!" He promised that within two months, Gusev's life would return to normal.

Gusev took the sealed letter №17/05 to the civil registry office. They didn't remove the entry from the death records but changed the data — replacing the living Gusev's date and place of birth with those of the deceased Gusev and again sending out letters along the chain. Vladimir Nikolaevich relaxed and went with his family to Anapa for a month in that same VAZ-2111, "the color of an aluminum pot." He took with him a document signed by the regional traffic police, stating that the data about this citizen's death were incorrect.

Vladimir Gusev didn't suspect that his resurrection would take another ten years.

II. A black shirt, a shoe, and part of corpse №312

Half a year before Vladimir Gusev learned about his "death," on February 6, 2004, partially blind Muscovite Alla Timofeeva was listening to the news on TV and learned about a terrorist attack between the "Avtozavodskaya" and "Paveletskaya" metro stations. The correspondent routinely reported that relatives of the deceased would receive monetary compensation from the state. Three days later, Timofeeva, along with her mother, went to the forensic morgue №4 and claimed that on that very day, her husband, Oleg Lun'kov, who had gone out for a couple of hours, never returned home. Alla's seeing mother, Lun'kov's mother-in-law, identified her son-in-law by a fragment of a checked black shirt, a shoe, and part of corpse №312—nothing else was left of the body after the explosion. Alla Timofeeva was recognized as a victim and given the shoe, shirt fragment, and remains. She buried all these at the Mius Cemetery on February 12—the same day when the alive Oleg Lun'kov was celebrating his forty-second birthday.

Oleg Lun'kov had been divorced from Alla Timofeyeva for quite some time, twice, to be exact, and hadn't seen her in four years. He was living a nomadic life, shuffling between his brother's place and friends' houses, earning a living as a taxi driver, and, interestingly, he never took the metro. On the morning of February 6, he watched the same news broadcast as his ex-wife. That summer, when pensioner Vladimir Gusev first learned about his 'death,' Lun'kov was bizarrely posing for a photo with his tombstone.

Lun'kov's dynamic relatives launched a bureaucratic blitz, hitting various departments — social protection offices, the pension fund, the Committee on Family and Youth Affairs, and the Savelovsky District administration. From Moscow's budget, they managed to snag all kinds of aid: financial support, compensation for lost property, funds to cover housing debts, burial assistance, pensions for two sons as they 'lost' their breadwinner, social benefits, and compensation for a terrorist attack — amounting to a total of 389,000 rubles (about $13,400 in 2004 exchange rates). They also got two tickets to the "Primorsky" resort in Gelendzhik seaside town, where Putin's palace is situated.

Lun'kov found out about his own 'death' in April 2004 while renewing his passport. By then, he had already been evicted from his apartment, and proving he was alive to the system took an entire year. Alla Timofeyeva learned about her husband's 'resurrection' at the prosecutor's office. She returned the funds she had received, sometimes pretending to sincerely believe in Lun'kov's death, and at other times threatening to sue him for faking his own demise.

The legal battle against Timofeyeva and her mother continued in the Savelovsky court until 2006. However, love triumphed — a forgiving Lun'kov convinced the judge that Timofeyeva had acted 'unintentionally.' He even tried to get his friends to back up his story, but they got tangled in their testimonies, and the court didn't buy it. Considering Timofeyeva's disability, two minor children, and an elderly mother, they were sentenced to two and a half years of probation.

III. An unmarked grave

Nikolay Puchkov's daughter had been preparing him for a peculiar conversation. "Dad, you're dead, and you've been buried," she told him. She worked at a radio factory in the tiny town of Kyshtym, 112 kilometers from Kopeysk, and by the end of May 2007, she found herself at the registry office for work. The head of the archive, a family friend, cautiously inquired about her father's health and revealed that a death certificate had recently arrived in his name. In a panic, she and her husband rushed to her father's country house, only to find him laughing off the news: "Well if they've buried me, guess we should order some pies." But when she mentioned that the registry office was expecting him, he realized he was indeed 'dead.'

The former design engineer still doesn't know who lies buried as "Nikolay Puchkov" in an unmarked grave under a modest wooden cross on the outskirts of the city cemetery. Law enforcement identified the body found in the spring on the street through witnesses' words and a photograph. Puchkov was evicted from his privatized apartment, his pension payments stopped, and his medical card at the clinic was archived.

In the registry office, Puchkov bought back his death certificate for 500 rubles. At the passport office, they almost confiscated his documents. "I had to run away with them," he recalls. During an interrogation at the prosecutor's office, they ended up calling in a police officer. "The police station is less than a kilometer from my house, and not a single officer bothered to check, even with the neighbors, about what's happening. But they told me it was a technical error and suggested I go to court." In court, Puchkov was denied assistance, with the justification that there is no law "About Returning from the Dead," so they couldn't consider his case. Frustrated, pensioner Puchkov turned to the newspaper "Kyshtym Worker," approached journalists, and started visiting his grave with TV crews. Standing knee-deep in the grass by the tilting cross, he told on camera how no one wanted to help him.

Through acquaintances, the pensioner found another judge who, fearing publicity, agreed to hear the case. Eventually, the chief of city police publicly apologized, and three officers were reprimanded and lost a month's bonus. Nikolai Puchkov received a compensation of three thousand rubles. At the trial, an MVD lawyer remarked that it should be enough, as he was featured on TV and written about in newspapers – what more could he want? To prove he was alive, it took Nikolai Puchkov only three months and five court hearings: declared dead on May 22, 2007, and "revived" on August 24, 2007.

However, after the trial, he started receiving fines for the person buried under his name. "The bailiffs decided, since Nikolai Puchkov resurrected, he should pay the old debts. They issued two execution orders, one with a fine of five hundred rubles for an administrative offense - my doppelgänger argued with a neighbor. The second fine was one million five thousand rubles: in 1997, Nikolai Puchkov and a friend robbed a house, served time in a colony, but had nothing to pay for the stolen goods." Thus, the former engineer had to prove he had never been convicted.

IV. The pure absurdity

Truck driver Andrey Popov didn't immediately grasp what the police battalion officers were telling him. By the morning of August 19, 2014, he was supposed to reach his hometown of Novokuznetsk, a major industrial city in southern Western Siberia, with cargo. Still, at one in the morning, he was stopped in the town of Leninsk-Kuznetsky for a standard check. His truck was taken for weight control, his documents confiscated, and then Andrey was informed that he was a corpse. "They were shocked themselves and didn't know what to do. Demanded my passport, started talking nonsense that I was driving with someone else's license or my brother's," he remembers. Popov was put into a police car, leaving his truck on the highway, and taken to the police station. He spent the night at the police station on the phone - calling his employer to retrieve the truck and his wife to come with documents to confirm his identity. "The police just shrugged: what can we do? You're free to go," Popov says irritably.

The next day, the trucker learned that he had died in December 2013 - just when, in Kopeysk, Vladimir Gusev finally went to court. Popov was deregistered from his apartment, the registry office couldn't explain much, and the Ministry of Internal Affairs promised to fix this "computer glitch" within ten days. Not waiting for the correction, he filed a complaint with the prosecutor's office, but there has been no response yet: "This is pure absurdity. I went to the head of the prosecution and said: here I am, really existing, and they just stamped a plain form stating that this person, me, is alive despite the database information."

V. A certificate of being alive

Vladimir Gusev filed a lawsuit against Russia in the fall of 2013 - a lawsuit against the Kopeysk prosecutor's office, the police, and the city administration, against the Ministry of Finance, the tax service, the pension fund, the primary department of the Ministry of Internal Affairs for the Chelyabinsk region, and the regional bureau of forensic medical examination. In the bureaucratic language of record-keeping, his demand is recorded as follows: "He requests to establish the legal fact that he is not the person who died in 2003" and "believes that the fact of his death is fictitious and unreliable."

The long-ago promise of the deputy prosecutor about a "normal life" did not come true. In 2007, Gusev received a call from the company director, where he moonlighted as a security alarm installer, who inquired about his health. Vladimir Nikolayevich said he was fine, to which the director replied, "Well, I have a problem with you." The tax service accused the director of financial fraud, as he had been paying salary to a dead person for three years. Gusev took the tax service's letter to the registry office, where they corrected everything and assured him: "This definitely won't happen again."

Gusev became a grandfather, returned to his job as a firefighter, received a letter of appreciation from the governor of the Chelyabinsk region for eliminating the consequences of a bromine leak on the railway, and in September 2013, he learned again that he was still dead. At work, he was told that the pension fund was not accepting a report from the whole department due to a "dead soul." His boss demanded a "certificate of being alive" or his resignation from Gusev. Amazingly, messages about Vladimir Gusev's death, sent by the registry office back in 2003, finally reached all addressees years later. Gusev got tired of it and found himself a lawyer.

Of the entire decade-long saga of his death, Gusev remembers with the most bitterness the court session on December 9, 2013. Half of the defendants did not attend the process, while the other half mocked him: "Man, who are you going against? All the city-forming power structures are here. Why are you looking for the guilty and redoing papers? Let's wait; you'll die anyway." Gusev partially won the case - the judge concluded that due to the illegal actions of law enforcement agencies, he suffered moral suffering, "encroaching on his intangible assets, such as life." He was awarded 50,000 rubles in compensation, but they did not restore his status as a living person - after all, he already had a passport, which confirms that Gusev was alive. The court also did not punish the guilty, but the defendants contested the decision.

A few days after the trial, Vladimir Gusev went to the pension fund and received an official document - incorrect information about his death date was removed from his individual account. But two weeks later, he was denied registration on the "Gosuslugi" website - "the RF pension fund did not confirm the existence of your insurance certificate." At some point, Vladimir Gusev's story reached the deputy general prosecutor of Kopeysk, Yuri Ponomarev, and at the end of January 2014, he gave an order to figure out the situation, punish the guilty and restore the citizen's legal rights. Instead, the court in Chelyabinsk reduced Gusev's compensation fivefold - such an amount "more corresponds to the nature and degree of moral suffering."

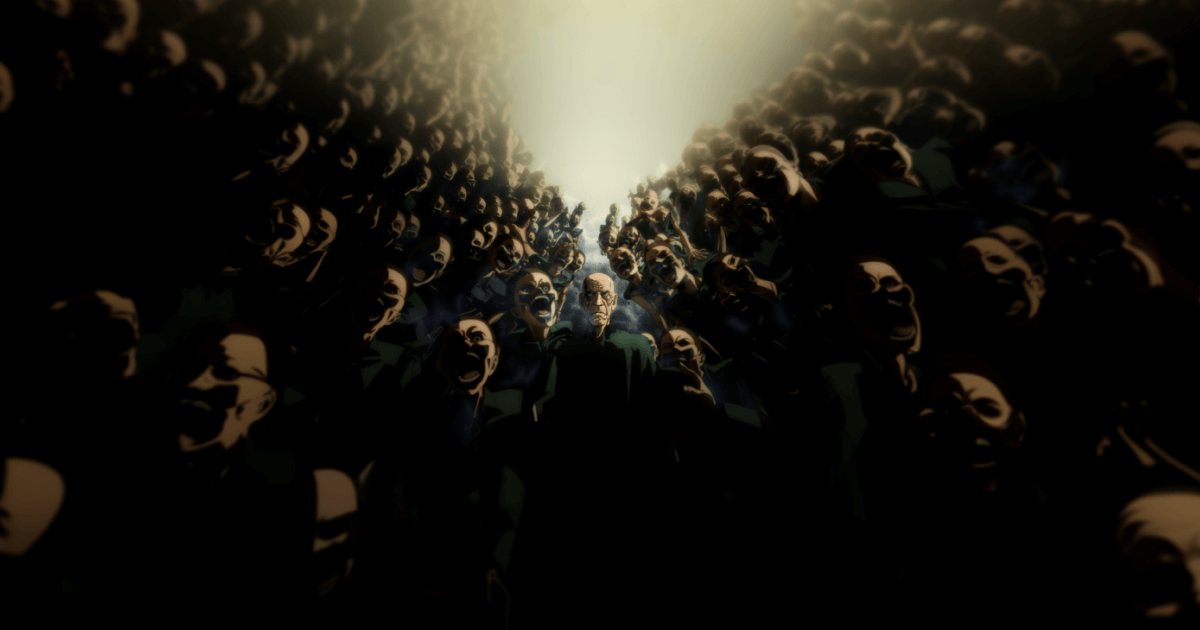

"What angers me the most is that no one apologized to me," says Vladimir Gusev. "No one is responsible for this pornography. A rude attitude towards a person and a dismissive attitude towards their duties. Everyone understands everything, but no one is accountable. It seems there is no moral damage. I didn't lose a hand or a leg; I can work - nonsense. It's probably time to get used to it; I guess I'll die sooner or later, and everything will finally come to its conclusion." The main feeling he experiences is shame: "I'm ashamed that here, on the periphery, an official is king and god, and a small person cannot break this barrier. I'm ashamed that I am a citizen of the Russian Federation."

Vladimir Gusev decided for himself: he no longer participates in population censuses, does not vote, interacts with the state at all, and does not go to elections. Gusev continues to work as a firefighter—"I protect the peace of these officials." And he says: since he is dead for them if there are any questions, let them bring papers to his grave.

He already has one.

1. Transform your identity crisis and own your story with an online narrative therapy session. Reduce anxiety and discover new perspectives through these collaborative conversations

2. Turn your life experience and passion into captivating media products with step-by-step coaching. I will guide you from ideation to creation, and together we'll craft your dream project

If you have any questions, feel free to reach me at most@hey.com