The Slowest Elevator in New York City

How Gay Talese Created New Journalism and Wrote the Greatest Journalistic Texts

Writer Gay Talese stands on the first floor of New York's Hunter College, passionately cursing the elevator that refuses to take him to give a lecture to journalism students. He spins impatiently in place, repeatedly pressing the button in irritation and looking around. Passersby linger their gaze on him: a magnificent silver-haired old man, tall and fit, in an expensive three-piece suit. Today, he wears a custom-made dark green tweed jacket, striped shirt, golden tie, cream vest, cufflinks, trench coat, and fedora hat, one of 60 in his collection. He stands out against the backdrop of stretched hoodies and club bombers, and this is precisely his secret. Right now, he needs information, and his unchanging dandy outfit will help him as usual. Talese turns his gaze to a young girl patiently waiting for the elevator in the corner.

"Are you a student?" the writer looms over her without warning. The girl, pressed into the corner, nods silently. "Yes? Do you study here?" She continues nodding. "Is this the only elevator in this building? Have you ever used it? Does it even work? Really? Why does it take so long? Does it always take this long?"

Talese feels outraged: in this great city, where elevators accelerate to 36 and a half kilometers per hour, he got the slowest one. The corridor becomes quite cramped — a fire service medic with two huge red bags joins us. Talese switches attention and immediately strikes up a conversation with him — by the time the cabin doors finally open, he already knows the firefighter's name, why he needs the bags (they contain mobile CPR training equipment), and where the demonstration will take place. If this damn elevator had gotten stuck, Talese could have written a text about the firefighter's life, but we safely reached the needed floor.

There’s a lecture to be given.

The evening's host, introducing Gay Talese to the audience, immediately makes a disclaimer — of course, our guest needs no introduction; you already know perfectly well who this is. There aren't many people in the hall, but everyone nods with exceptional dedication. Talese is a living legend, the man who in the 1960s created "new journalism" to replace news journalism: instead of dry info-style, a radical approach to materials, complete immersion in the topic and heroes' lives, techniques borrowed from great literature: scenes, dialogues, descriptions, internal monologue, switching between first and third person. He is one of the last living giants of American nonfiction prose of the past century. He inspired people whom we consider exemplary writers and reporters: Norman Mailer, Truman Capote, Joan Didion, George Plimpton, Gene Stein, Terry Southern, and others. He spends a decade collecting material for each new book—and manages to get inside his characters' heads, under their skin, and study them thoroughly.

Introducing Talese, the host omits important but not the most pleasant details — before the students stands a cursed star of American journalism, a stubborn and willful man whose charisma disarms, but whose books have caused many scandals. In February 2024, Talese celebrated his 92nd birthday, and today, as the Paris Review writes, he occupies a unique place, remaining simultaneously legendary and misunderstood. His nonfiction "Honor Thy Father" became the basis for the series "The Sopranos." Because of the book "Thy Neighbor's Wife," for which he spent several years managing an erotic massage salon and visiting swinger colonies during the 1970s sex revolution, they canceled him, and his wife temporarily left him. And the portrait essay "Frank Sinatra Has a Cold," for which he never managed to speak with the famous singer but talked with a hundred or so people from his entourage, people have called the best magazine text in history for half a century, and, together with his other texts and books, they study it worldwide.

But Talese waves off all these accolades — he never liked the nickname "Father of New Journalism," which his friend and writer Tom Wolff bestowed on him, he doesn't care about honors, doesn't care about curses — at least, that's what he assures. Talese got into all this to tell stories of ordinary people and their failures, and today he will answer any questions from the audience — of course, reducing everything to several truths that he repeats over and over in all conversations, speeches, and interviews. The first truth — he has been isolated from others since childhood, has been and remains an outsider all his life, who knows that everyone has a story, and it's important for him to extract it, because if he doesn't tell these stories, no one will tell them. The second — he knows how to extract these stories from people because he was born into a tailor-immigrant's family, grew up in an atelier, and this taught him to hear everything, notice everything, and dress well, which allows him to talk with anyone. The third — in his work, he always scrupulously seeks an answer to one simple question: what is it like to be you? How do you cope with your failures, defeats, with people despising or misunderstanding you? How do you compensate for this? "Most people are absorbed only with themselves," Talese once told me — "They will never think about you. But I will think."

Gay was born February 7, 1932, in Ocean City, New Jersey, to a family of Italian emigrants. He remembered his hometown as conservative, Protestant, and right-wing: alcohol was banned, you couldn't go to the ocean beach without a shirt, everything was subordinated to religious orders, and a Ku Klux Klan cell operated on the streets. It was here that Talese formed as a storyteller, convinced that the author's duty is to seek out small stories and discern the broader context behind them. He himself grew up against the backdrop of a big context: World War II was raging, dad's brothers were fighting in Italy in Mussolini's army, and the patriotic, predominantly Irish population of Ocean City hated the small number of Italians and treated them like dirt. Moreover, the distant war permeated everyday life: merchants sold goods by rations, young men went to the front, and they painted the promenade lights black so German submarines, which had reached American territorial waters in 1942, couldn't see them. In social isolation, in growing up within a minority, in alienation, Talese found his superpower. He became an observer who hungrily seeks stories of loss and failure.

His family kept a women's clothing store and a men's suit atelier, which the Taleses had opened on both sides of a building of a bankrupt local newspaper they had bought on the main street of town. They lived there too, on the second floor — Talese still remembers the high office steps and rooms where huge typesetting machines used to stand. Every day after lessons at Catholic school, Gay helped dad and mom in their stores and listened. Car center owners and dealers, officials, school and enterprise directors came to dad, their wealthy wives came to mom for beautiful dresses. Women wandered around town, came for fittings, and told about their lives — experiences, failures, discoveries, gossip.

Talese says he mastered the interview genre by observing his mom and her communication with clients. He learned from her to listen carefully, with patience, acceptance, and reverence. And not to interrupt when people can't explain themselves, because it's precisely in such moments that they reveal themselves best: pauses, hesitations, and topic switches can tell more than any words. In the service sphere, he explains, there's always an element of certain servility — even if people don't communicate with you too kindly, you must be exceptionally polite, because these people give you money. These were lessons from mom, a businesswoman who supported the family — dad was an artist, created, and didn't know how to sell. But from him Gay learned to create art — to work with texture, like a tailor with fabrics, to sew real stories together so they read like a unified literary work — a journalistic story. Talese says it this way: "As a journalist, I'm a tailor."

He got into journalism while still a college student, through a stupid coincidence — decided to ingratiate himself with the baseball coach so they would let him off the bench more often, and took on dictating summaries from school matches to the local Ocean City Sentinel-Ledger newspaper by phone — pure formality, a couple of lines. But such work quickly became boring, and the teenager started sending typewritten author reports to the newspaper; after the seventh text, they offered him to run a weekly sports column. By college graduation, he had published 311 texts. Talese's style was already visible in them—a complete lack of interest in the news itself and focus on human actions and experiences, drama, and defeat.

Gay went to study journalism at the University of Alabama, became sports editor of the campus newspaper The Crimson White, and started a column "Sports Gay-zing." After university, he moved to New York and got a job by sheer audacity as an errand boy at The New York Times. The newspaper filled him with delight: a huge hive of several hundred smoking journalists typing on typewriters, bustle, noise, conversations, and elevators — much faster than this damn elevator in Hunter College. At 21, he published his first text in the newspaper: a sketch about a colleague who was responsible for selecting and broadcasting headlines in the editorial building. Soon, they drafted Talese into the army and sent him to Fort Knox military base in Kentucky. In the tank troops, they quickly realized that he would be no good in formation and transferred him to the army newspaper "Inside Turret." Soon, he started his own column — "Fort Knox Secrets." Two years later, returning from service, he restored his position at The New York Times as a sports journalist and wrote hundreds of texts — about boxer Floyd Patterson alone, he published 38 short sketches.

But excessive scrupulousness and unwillingness to work at a news pace led to them transferring Talese from department to department at The New York Times, until he got stuck for a year in exile in the obituaries department — there they didn't let him write more than a few paragraphs. For Talese, this was real torture: he wanted to do major journalistic prose, tell stories that live for years, decades, not a day like ordinary news, talk about people whom the press has neglected, not chase news hooks — because all news, Talese rages, comes down to someone saying something and someone somehow reacting to it. Or simply dying.

Despite his passion for telling stories, writing was always unbearably difficult for him. Gay compares working on texts to trying to pass a kidney stone (very painful) or driving a truck at night, at high speed, without headlights turned on (you lose your way, fall into a ditch, spend the next ten years stuck there, dirty and stinking). But Talese is a Catholic, and for him, nothing not paid for with suffering has any value.

After the army, he settled in a four-story apartment building on Lexington Avenue, three minutes' walk from Central Park. In 1959, he married book publisher Nan Talese (maiden name — Ahearn), with whom they are still together. Gradually, the Taleses bought out the entire house and have lived in it to this day. Here too, in the spacious living room, I met Talese in April 2014, during my first trip to the USA.

I was a poor Russian freelance journalist then, wrote big stories for publications that no longer exist, and hungrily sought any knowledge and skills that would help me do this work even better, better than everyone. I catalogued literary devices, studied different approaches to designing and classifying plots, and collected successful excerpts from others' texts. I spent most of my time and effort studying story structure and composition — I was obsessed with this topic. The question that always concerned me was — how best to compile and bring together on paper a huge amount of information so that the text reads easily, is logical, clear, but at the same time draws in, intrigues, and grabs the reader by the scruff from the very first sentence. I read about the Hero's Journey, studied textbooks on narratology — the scientific discipline that studies narrative, collected examples of text plans and works by different writers, and experimented with each of my new texts. Somewhere in the middle of this search, I stumbled upon a listing of the best American magazine essays, and learned about Gay, and if anyone understood everything about text structure, it was he.

When I realized with surprise that Gay was continuing to work, I found his email, wrote a letter, and suggested a meeting while I was in New York — not really counting on anything special. He instantly replied — said he didn't feel well because of a mild intestinal flu, so he could only invite me over for an hour.

I had never felt stupider than when I stood under the Taleses' door with three cardboard coffee cups in a holder — after all, you had to bring something, but what do you bring to strangers living in their own four-story house by Central Park? Talese opened the door — as always in a perfect suit — held a condescending, uncomprehending gaze on the cups, asked what this was, and told me to leave the gift somewhere in a corner, never to even touch it. We sat in armchairs, Talese took out a pen and a stack of narrow cardboard cards that he had cut from shirt hangers from the dry cleaner from his inner pocket, and began recording my answers to a machine-gun burst of questions there. Who am I? Where am I from? What do I do? How much do I earn? Who pays for my housing in Moscow? Do I live alone or with parents, or with a close person? Do we pay for housing together? What are my parents' names? What do they do? How many brothers and sisters do I have? What do they do? Do they live alone? Do they pay for their own housing? Am I Bob Dylan? No? Then why do I dress like Bob Dylan? Why am I in sneakers?! Where is my suit? Do I have a suit? I should have a suit if I want to be a journalist and tell stories. An expensive suit is a pass into the world of stories. The hour-long meeting grew into dinner at one of the neighboring restaurants — every day the Taleses must go have a couple of cocktails and look at people, dinner—into friendship, a ten-year correspondence, and now this book.

Every time I come to New York, the first thing I do is see Talese. We discuss journalism, and I listen to grumpy comments about my appearance. I love jackets, but my sneakers and jeans constantly drive him crazy — he almost yells at me: How could you? He's indignant, but with love. The idea to publish his works in Russian appeared to me almost immediately after we met. It's surprising, but at that time Gaywas was not known to Russian-speaking audiences. It took me 10 years to finally make the book, "Frank Sinatra Has a Cold and Other Stories," happen.

All these years, Talese has continued to work and observes strict discipline every day.

He wakes up in the bedroom on the third floor, doesn't say a word and doesn't greet Nan, silently goes up to the dressing room on the fourth floor, puts on a fresh crisp shirt, three-piece suit, tie, cufflinks, leaves the house and goes down the steps to his basement — a former wine cellar that he calls the Bunker. In the oblong Bunker, there are more meters than in an ordinary Manhattan apartment; there are no windows, but there is a small bathroom, a kitchenette, several sofas, two huge desks, a typewriter, a gigantic and ancient Apple monitor, chairs, and cabinets packed with boxes to the ceiling — Talese's archive. The writer changes into a comfortable cashmere sweater and scarf or neck scarf, and makes himself a light breakfast — orange juice, coffee, muffins.

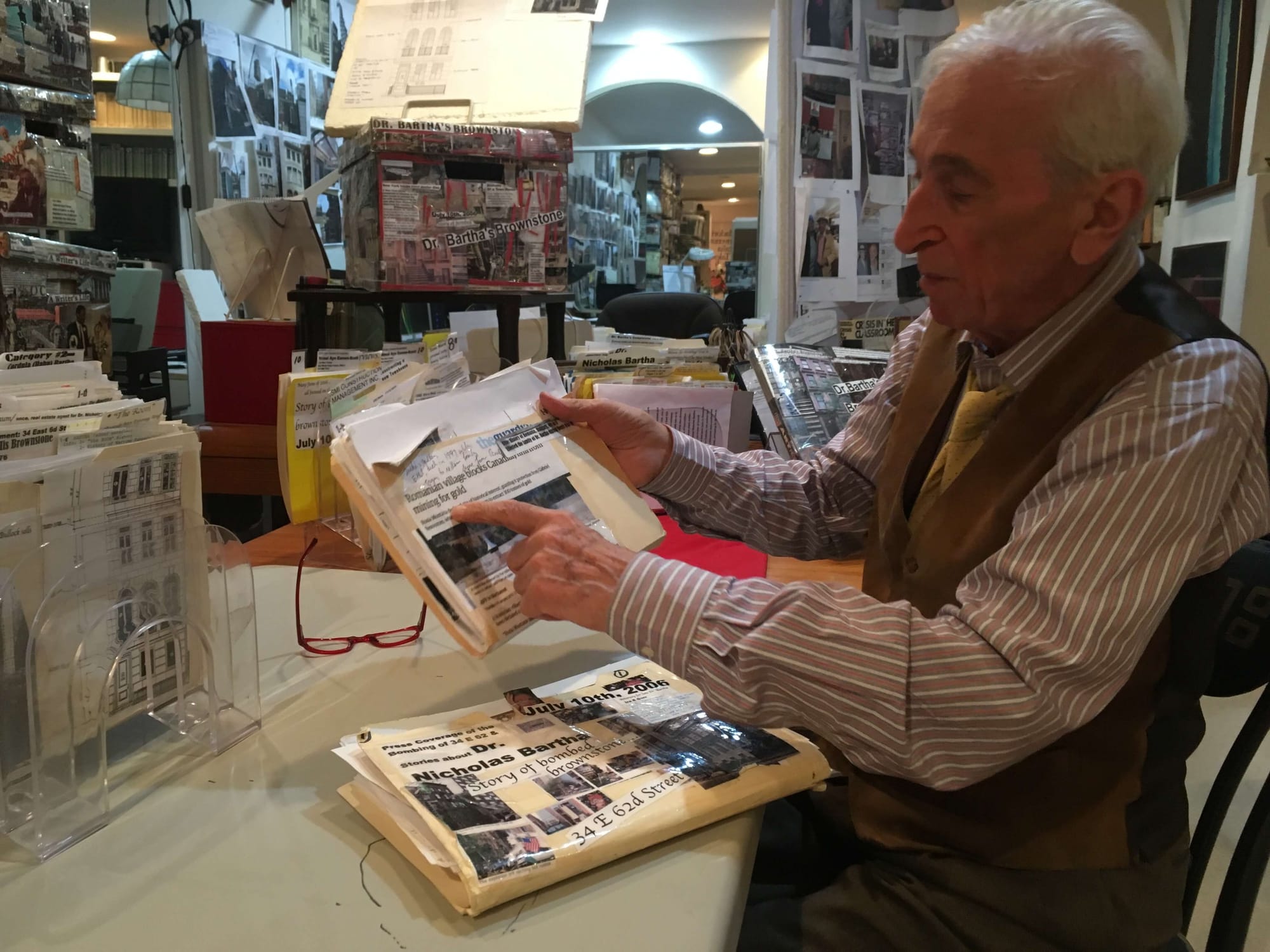

He surveys his archive: in each box, a collection of folders with photographs, materials, research results, excerpts and clippings from books and articles, text plans, and detailed notes about all past days. Every evening before sleep Talese reviews notes on cardboard cards, if he kept them that day, or recalls everything that happened to him, and records everything on the typewriter: whom he saw and talked with, where, when and at what time, how much dinner cost, who wore what, what he thought and noticed, what people around were called, who did what, what the weather was like, addresses, details, nuances, how the interview went (if there was one), what the hero said, and what he kept silent about. And files the typed notes in the archive. Days are organized into weeks, months, and years. He can return to the past at any moment and describe in detail what he saw several decades ago. Each box is pasted over with photographs, pictures, magazines, and newspaper pages — this is a thematic collage that Talese cuts out when he thinks about a story and how he will sew together the fabric of the text. He spends a good part of the day in the Bunker, goes up home for lunch, and in the evening — without exception — a social outing to a restaurant. In the Bunker, Talese wrote all his major texts — magazine essays that he switched to from newspaper work, and books.

In 1964, he published the nonfiction novel "The Bridge" — the story of building one of the world's largest suspension bridges, the Verrazzano-Narrows, connecting Brooklyn and Staten Island. In 1965, he left The New York Times and has remained a freelancer to this day. Already in 1966, when he was 34 years old, Talese published his three most famous portrait essays in Esquire. "The Silent Season of a Hero" — about Joe DiMaggio, the great baseball player and Marilyn Monroe's ex-husband. "Mr. Bad News," which Talese calls his best text, is about obituary writer Alden Whitman. Finally, "Frank Sinatra Has a Cold" — a profile for which Talese talked with two hundred people, but never managed to exchange even a word with the singer himself.

He actually didn't want to write about Sinatra, since he was already a big star whom the press talked about every day. But Gay didn't argue with the editor, a former Marine, and went on assignment to Los Angeles. Today, he assures that the secret of his acclaimed text is simple: he was able to see in the influential superstar, surrounded by countless entourage, an ordinary, tired man who has his own failures and weaknesses.

Not counting collections of essays and profiles, Gay Talese wrote nine books. In 2016, Talese published "The Voyeur's Motel," a book about Gerald Foos, a motel owner who spent 30 years spying on how his guests had sex and meticulously recorded his observations in a journal. Same year, a documentary film Voyeur came out on Netflix. The team spent several years filming Talese and Foos in the final stages of preparing the book; however, the publication ended in scandal — Washington Post journalists caught the hero lying and falsifying facts. Talese, although he had mentioned more than once in "The Voyeur's Motel" that his hero was not the most reliable narrator, even thought about refusing to promote the book, but didn't. But Steven Spielberg and Sam Mendes abandoned their plans to shoot a screen adaptation.

In September 2023, Talese released a new book — "Bartleby and Me: Reflections of an Old Scrivener"; in addition to essays from past years, it included a new story that had occupied his consciousness for the last 17 years — the story of Dr. Nicholas Bartha. Bartha, a native of Romania, fled from the communist regime that had taken away his family's house, achieved success in America, and bought himself a four-story building in Manhattan, on the neighboring block from Talese. In 2006, Bartha blew himself up along with the house so the building wouldn't go to his ex-wife. All these years, Talese collected Bartha's story bit by bit, observed the resulting wasteland and the people around. I was even able to help Talese a little with research for this text: the new owners of the land plot turned out to be people from Russia, accused of large-scale corruption and fraud.

Talese's works are remarkable not only for how they are written, but also for how much he manages to learn about his heroes — he gets as close as possible to them and says that he doesn't need boundaries. For example, he wrote letters to gangster Bill Bonanno for four years straight and suggested talking, until he finally replied—then the writer spent five years in close communication with Bill and his family, and only after that wrote "Honor Thy Father." "It's like courtship," Talese explains to me. — "You need not rush, behave well and act carefully, not like an ordinary journalist-asshole who just needs to quickly screw around for a short fling." At the current exchange rate, Talese earned 8.1 million dollars on the book and put most of the fee into an educational trust fund to pay for the education of his two daughters, Pamela and Catherine, and Bill Bonanno's four children. As a result, all the gangsters’ children were able to build careers not in crime.

It was this approach at the time that led to Gay Talese being cursed. The release of the book "Thy Neighbor's Wife" in 1981 divided his life and career into before and after: the publication brought the journalist both the biggest money of his life and the biggest storm of criticism, whose echo still sounds. For ten years, Talese collected material, immersing himself in the wilds of the sexual revolution. He became a nudist, attended sex parties, orgies, sex retreats, and sex colonies, visited erotic massage salons daily, and then became manager of one of them, to better understand his heroes and guests. "Of course, I was in the thick of things! — he exclaims. — You don't think that I'll cover an orgy sitting in some separate fucking media box?! Yes, it's like there are always two guys inside me, I'm such a schizophrenic character: simultaneously reporter, observer, and participant, and I always survey the room looking for a story and how to describe it." Critics and feminists fell upon Talese with murderous accusations of impermissible methods of collecting material and inappropriate attitude toward his wife, who hated the book "Thy Neighbor's Wife" and separated from him after its release. For the next ten years, magazines didn't publish Talese, and his therapist told him that he had committed literary suicide. He fled to Italy, lay low, and studied his family's history — the material later became the basis for the book "Unto the Sons." He and Nan got back together. The secret of a long marriage, Gay says, is to never lose respect for each other and have two separate bathrooms.

***

After the lecture, we go with Talese back to the ill-fated elevator, and a gray, disheveled man catches up with us. He only manages to say "Hey! Gay!" and Talese, seeing him, throws out: "Oh, no! Yegor, let's run, we won't wait for this elevator!" Talese jerks sharply from his place, unexpectedly briskly runs to the fire escape, and swiftly rushes down the steps. I follow him, behind us — the man shouting "Gay! Gay! Wait! Do you remember me? Gay?!" We get out onto the street, it's already dark, somewhere, as usual in New York, a police siren is wailing, clouds of steam are bursting from underground, and passersby are looking around at Talese.

We break away from the chase. What was that? Who is this person? Talese doesn't want to talk about it — and suggests going to dinner. In the restaurant, he eats steak, salad, drinks two martinis, beer, and polishes off with a scoop of vanilla ice cream, and questions people at the neighboring table. For him, the restaurant is a theatrical stage where he can observe life, roughly like his parents' store and atelier; a place where people open up, and he can strike up a conversation with anyone. "I'm a voyeur. I'm an observer," he explains to me. — "I want to know everything about people, even if they don't consider themselves interesting. The other day, I saw an old homeless woman on the street. I needed to hurry, and I couldn't talk with her. What was she 40, 50, 60 years ago, when she was younger? She could have been attractive, maybe she worked in a store, maybe she was married. Look at her now! She's on the street, completely gray, she doesn't even extend her hands, she just has cups standing on the sidewalk, and she sits in trash opposite the store. Maybe we could find her old photograph? Maybe she had a daughter, or a lover, or someone else. Maybe she used to be a reporter? A dancer? Who knows? Why did she end up here? These are stories."

Gay Talese is 93 years old. In 2024, his new book came out, "A Town without Time," a collection of his texts about New York, which he has long called the city of the unnoticed. Before submitting "Frank Sinatra Has a Cold and Other Stories" to print, I asked Talese what he thinks about the book that we conceived almost ten years ago finally coming out. He asked me to convey the following: "I'm happy and, actually, proud to finally be published in Russian. In the language of some of the world's best writers, and people who have always aroused my admiration." He continues to observe strict work discipline and goes down to the Bunker every day to write: "At such an age you think all the time that you'll be dead in a week, so you need to be one step ahead."

The most analog person in the digital world, from which, according to him, he has fallen behind by fifty years, he despises tape recorders, haste, and 40-minute superficial conversations with celebrities. He also sends a message to young authors and journalists: "You should be able to write small stories, and find big ones in them. And write so that it can all be read in 2035. You should have something like Chekhov's stories or his plays. That fucking 'Cherry Orchard,' it's already a hundred years old, and they still perform it in New York! America is already tired of this damn play, but they keep showing it! Do the same!"

He remains true to himself to the end: works at his own pace, collects stories, will write every day until death, and does not plan to apologize for anything.

Gay Talese remains the slowest elevator in New York City.