Ballet, Bribery, and Bloodshed: The Fall of the Bolshoi Theatre

Death, acid attacks, violence, sex, corruption, and hatred are the main symbols of modern Russia, irreversibly rotten from within.

In the shadow of the Bolshoi Theatre, Russia's biggest and most internationally well-known cultural institution, a microcosm of the nation's violence, corruption, and barbarity unfolds. I investigated the Bolshoi for over a year and delved deep into the heart of darkness. Beauty and ugliness coexist in a symbiosis here, and the quest for money, power, and fame can lead to deadly outcomes.

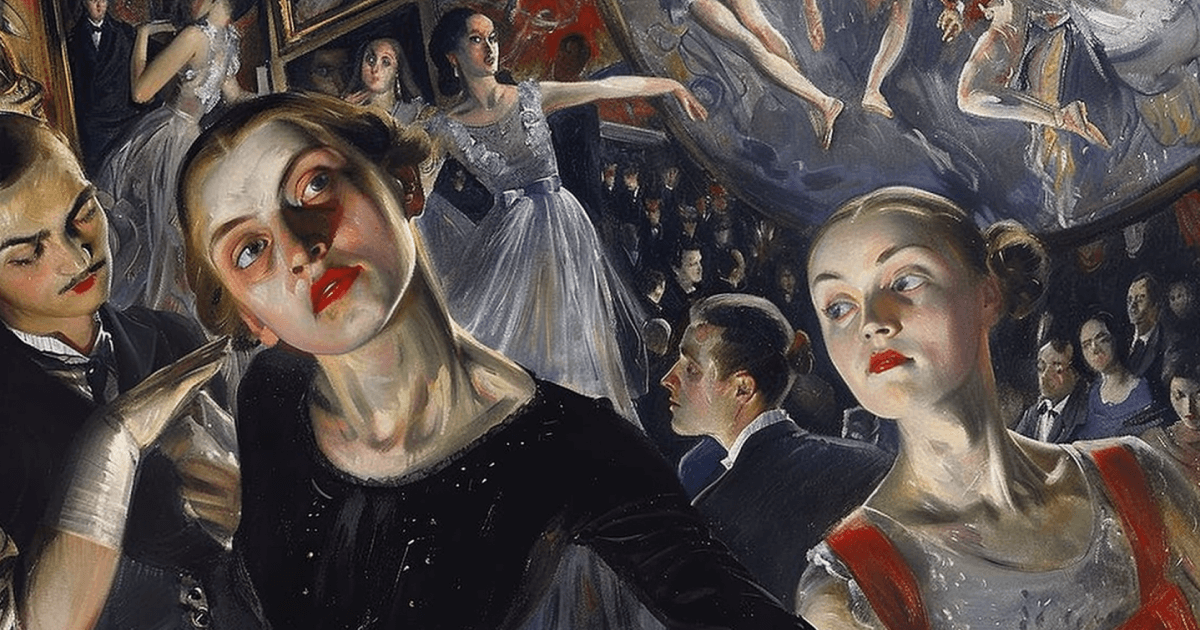

Mr. X, the general director of the Bolshoi Theatre, Anatoly Iksanov, steps back and leans against a velvet banner with the theatre's logo. The blinding June rays, piercing through the glass dome of the atrium, play on the golden frame of his glasses, mustache, and self-satisfied smile. A crowd of journalists presses on Iksanov. Shouting over each other, they ask the same questions: "What will now happen with the principal dancer Nikolai Tsiskaridze?" and "How did you manage to deal with him?" But Iksanov smiles and slowly backs away. He and his colleagues had just announced that the current season would close in a month, outlining plans for the new 238th season, but refused to discuss anything beyond creative plans.

The 2013 season was very challenging.

On the night of January 18, 2013, the artistic director of the theatre had a mixture of acid and urine thrown in his face, causing partial blindness and necessitating over twenty eye surgeries and extensive treatment in Germany. The lead soloist is in jail, accused of organizing the attack. His civil wife, a ballerina believed to be the reason for the acid attack, leaves the theatre. The head of the ballet company, who was also involved in the attack, was fired. A premier dancer aggressively quarrels in the media and sues the theatre. A prima ballerina moves to Canada, fearing to return to the country because of threats. A mime artist is beaten and robbed. A former tenor is arrested for embezzling $1.3 million. The theatre is accused of organizing a brothel. The Ministry of Internal Affairs announces the theft of $2.8 million during the theatre's reconstruction. A month later, a violinist dies in the theatre, and two months after, the head of strategic planning is fired.

In the thirteen years of Iksanov's tenure as general director, this was the loudest year, and in this year, the State Academic Bolshoi Theatre definitively moved from the "Culture" section to the crime chronicles, from high art to the realm of mass pop-culture. In its everyday rhythm, the Bolshoi Theatre most resembles a territory under a counter-terrorism operation regime.

The state of the Bolshoi Theatre, the Kremlin's pride and symbol of modern Russia, where money, power, primary business interests, jealousy, and fantastic ambitions intertwine, can be viewed from endless perspectives. It is a boiling point, ready to explode, and the world-famous attack on artistic director Sergey Filin became that explosion.

The story of the attack could be told like "Twin Peaks": owls are not what they seem, Laura Palmer was killed by the collective evil of a backwater town, and she was not so simple herself. Or like "Game of Thrones": Medieval times, bloody battles for the Iron Throne, no positive characters, winter is coming, darkness approaches, and everyone is frantic with their machinations, ready to slit each other's throats. Finally, a classic Agatha Christie detective story: the gardener is the murderer, but everyone in this room has a motive. Multiple variations.

But today, Iksanov has won. He has rid himself of at least one problem. He, therefore, smiles: in ten days, the contract of the scandalous principal dancer Nikolai Tsiskaridze, whom he calls a "boil" and accuses of fostering an atmosphere of evil in the theatre, will not be renewed. Tsiskaridze will no longer work at the Bolshoi. "You don't know? – smiling even wider, Iksanov finally answers the crowd. – I've already decided. Haven't you heard? I've sorted it all out. Everything's decided." And, satisfied, he leaves.

He doesn't know yet that in nineteen days, early in the morning of July 9, under the pouring Dublin rain that flooded the entire center of Moscow, he too will be swept away by an acid wave. In another hall, another resignation will be announced – his own.

Yes, it was a difficult season indeed.

I. The War for Roles

Prima ballerina Svetlana Zakharova, a former State Duma deputy from Putin's "United Russia" party, synonymous with the word "ballerina," was one of the few who did not applaud artistic director Sergey Filin when he spoke at the traditional annual company gathering on September 17, 2013. Filin had returned from Germany three days earlier after treatment and was to make his first public appearance before colleagues since the attack. Zakharova sat in the fourth row, clearly seeing Filin on the raised orchestra pit of the historic building, at a long table alongside the new general director Vladimir Urin, then Putin's Minister of Culture Vladimir Medinsky, and the head of the theatre's board of trustees and the Russian Olympic Committee, Alexander Zhukov. She saw how Filin read his notes, saw him stand up and take the microphone as the hall erupted in ovations. Zakharova did not move; he only glared at Filin with contempt and occasionally mimicked his speech mannerisms softly.

Two months earlier, Svetlana Zakharova was supposed to perform the role of Tatiana in the premiere of "Onegin," a role she had dreamed of for many years. Ten years ago, when Zakharova was lured from the Mariinsky Theatre in Saint Petersburg, Russia's second most crucial theatre, Iksanov guaranteed her special conditions, including the right to dance in the first cast of any show she was involved in. Two weeks before the premiere, Zakharova was suddenly assigned to the second cast, with the talented but young lead soloist Olga Smirnova, who had been at the Bolshoi for only two years, placed in the first. The official version is that it was the decision of the producer, the Cranko Foundation, which owns the rights to "Onegin." The unofficial version states that it was Sergey Filin's decision; they say he "completely lost his head" in the theatre over Smirnova. Smirnova is married to the son of Dilyara Timergazina, Filin's advisor, and Filin actively supports her. Zakharova was offended and refused to dance in "Onegin" at all. And there's nothing worse than being offended over roles in the theatre.

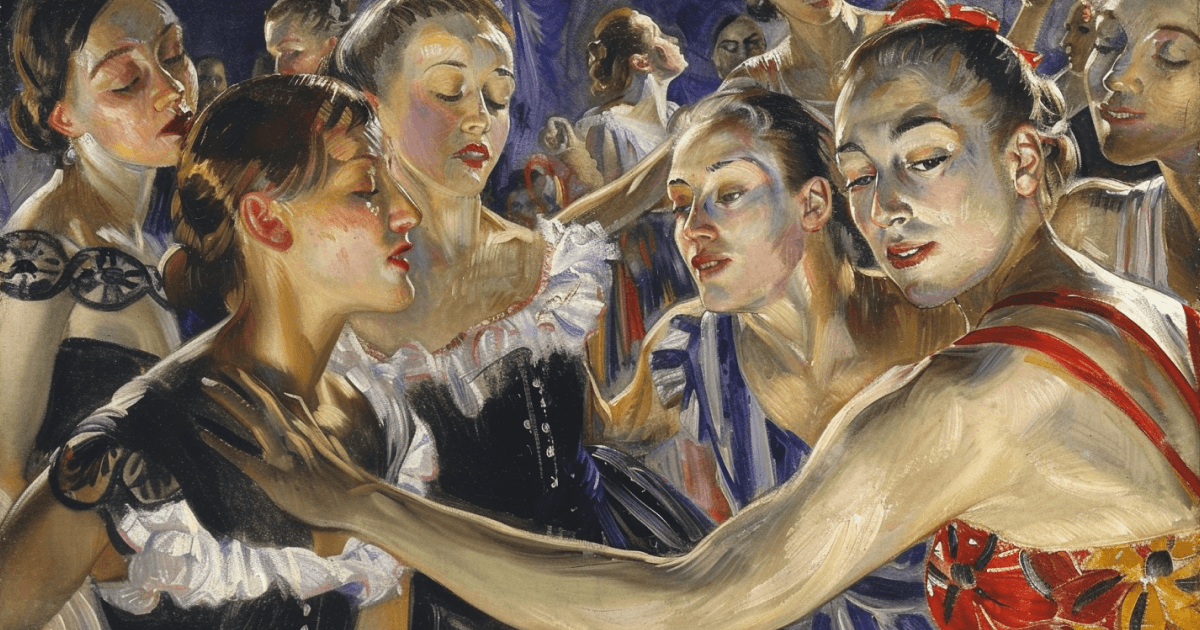

Ballet artists virtually live in the Bolshoi Theatre: six days a week, one day off – Monday, ten and a half months a year under the ballet master's baton. They have almost no non-ballet friends; everyone in the troupe sleeps with, marries, divorces, and seeks revenge on each other. Mornings are for classes: standing in front of mirrors in sweat-soaked tights, crumpled shirts, and pants, just woken up, without makeup, with calluses and bruised toes, repeatedly practicing the same movements. Arabesque, brisé, plié, relevé, fouetté, one-two-three, arabesque, brisé, plié, relevé, fouetté, one-two-three. Break, rehearsals, cafeteria, a bit of sleep in the dressing room, personal rehearsals, show rehearsals, the performance, home. And there's nothing else in life: the ballet barre, coveted and not always accessible roles, their closed society, and a life scrutinized by colleagues under a magnifying glass.

Ballet artists are considered unhappy people compared to professional athletes, and it's said that ballet is pain, a torment in colors. There is no childhood, no broad horizons, no foreign languages, only devotion to beauty.

"I pity them," says a theatre administration employee. "They are fanatical about their work, have laid their lives on physical exhaustion, and limitations, and remain with their childhood cruelty, seeing everything in black and white. And they have to fight a lot for each role, constantly proving to themselves and others: who looks better, who has better data, who got which cast and roles, who gets longer and louder applause. Because if you're not better, you're worse."

Ballet careers are short—just twenty years—and then you're out of circulation, with the peak of form lasting at most five years. There's a clear class hierarchy, so you can't delude yourself into thinking you're good enough: You're still in the corps de ballet, and she's the queen of the swans. It's either me or her.

Competition and fanaticism breed jealousy and quarrels. Long before the attack on Filin, Iksanov said that ballet artists in the Bolshoi troupe coexist poorly, "elements of hatred are present," artists refuse to dance with each other and constantly act capriciously because they've been cultivated for decades to believe that since they're in the Bolshoi, they can behave this way. The new director, Vladimir Urin, asserts that a severe star disease in the theatre needs to be combated because it's "shamelessness."

When it comes to quarrels and intrigues of the Bolshoi Theatre, the first thing that comes to mind is the urban legends about broken glass in pointe shoes. Ballet artists only chuckle at this mythical glass: these are just childish pranks because the actual daily ballet routine of the Bolshoi recounted to an outsider would seem like a manual for conducting guerrilla warfare under occupation – sabotage, positional battles, surrounding oneself with allies, friendship against each other, denunciations, slander, collective gatherings to sign protest papers, snitching, incitement, black PR, and rumors. The law of the jungle, and – in this serpentarium- no other amusements exist.

Boris Akimov has been working as a ballet master teacher at the Bolshoi since 1989, headed the Moscow State Academy of Choreography, was the artistic director of the Bolshoi ballet troupe from 2000–to 2003; and after the attack on Filin; he headed the newly created artistic council of the theatre. Akimov claims that artists have changed significantly after fifty years of working in ballet. "The communication culture was different before – even if you were dissatisfied with something, you would go around the corner, cry, swallow the lump, and go to the hall to work. Relationships have always been complicated, but there was always respect," says Akimov. "Now the kids are very focused on solving their tasks, sometimes the wrong ones, and they will argue, go through unsightly paths. There weren't such several quarrels or discord before." Akimov says that the artistic director's job is hard; his decisions can't please everyone, but "it's necessary to place the chess pieces correctly."

When Sergey Filin was attacked, one of the first motives was the war for roles. On condition of anonymity, Bolshoi employees explain why. "Filin is a man of Putin's formation, lives not by the law but by concepts: you lick my ass – you dance. Don't lick – you don't dance, I will oppress you. And all this in plain text," claims an administration employee. According to the source, the artistic director removed the undesirables from shows, pushed them to the back of the stage, and didn't take them on tours, which brought significant income to the artists. "All this lawlessness couldn't go on indefinitely," believes an employee of the artistic production part. "Guys work like convicts, get nothing from it – no feedback, no money, nothing. This tension and dissatisfaction were growing and had to burst out. It's a pity it burst out like this."

As for ballerina Svetlana Zakharova, a week after she learned about her transfer to the second cast of "Onegin," she met with Vladimir Putin at the opening of the Universiade in Kazan, and three days later, Anatoly Iksanov was fired as the head of the theatre after 13 years of service. "It seems he never understood that Filin ultimately set him up," concludes a theatre administration employee.

II. Money and Corruption

The State Academic Bolshoi Theatre is a separate state in the very center of Moscow, opposite the Kremlin. It comprises five buildings, two main stages, and several secondary ones, endless labyrinths of corridors that take months to navigate without getting lost. Initially, you can't take the same route twice: this elevator goes up to the seventh floor, then down the corridor through the large rehearsal hall, and down two flights of stairs; take the tiny elevator, not the big one, or you'll get lost, three floors down, then straight ahead, left, left, left, then down the stairs, then through the glass corridor - and you're there. Three and a half thousand employees. It owns a kindergarten, museum, clinic, newspaper, construction, summer cottage cooperatives, three trade unions, video studios, a publishing house, and a passport and visa department.

In 2000, when Anatoly Iksanov was appointed the Bolshoi's general director, the theatre was living in poverty. The Bolshoi even held awkward charity evenings and auctions, selling Dom Pérignon from 1975 and Swiss watches to collect money for at least a cosmetic renovation. Today, the Bolshoi Theatre means incredible, exorbitant money. The theatre's annual budget has a separate line, and in 2023, the Bolshoi received $53.5 million from the treasury. This does not include profits from expensive tickets, the annual presidential grant, sponsor support, and contributions from the board of trustees, which provides for oligarchs Roman Abramovich, Viktor Vekselberg, Ziyavudin Magomedov, and other significant people in business.

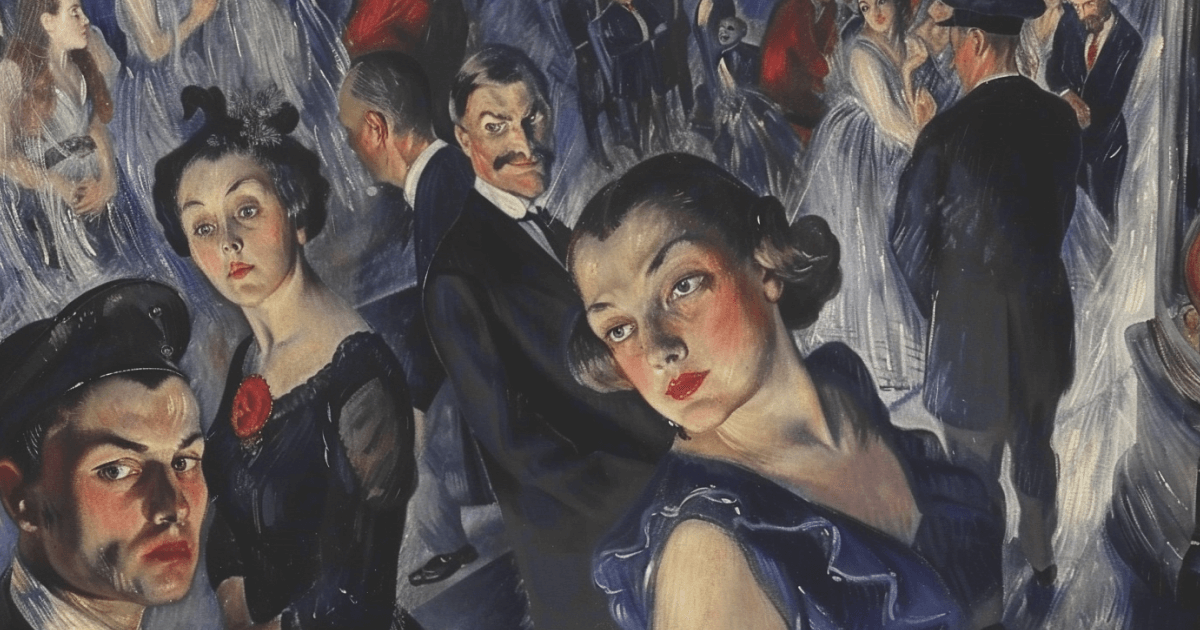

Party nomenclature, officials, the presidential administration, ministers, security forces, wealthy sponsors and rich patrons of artists wanting to influence the repertoire, wives of affluent figures, ticket mafia and scalpers, proxy viewers, insane fans - everyone is concerned with the Bolshoi Theatre. Anatoly Iksanov once equated the Bolshoi Theatre with orders from the Russian defense complex: many want to latch onto the enormous budgets, leading to noisy battles for thrones at different levels and scandals, corruption, and theft.

"In all theaters of Russia, there is theft. The main expense item is scenery and costumes, all costing astronomical sums," shares an anonymous theatre administration employee. "In reality, everything costs much less. Choir artists are brought shoes allegedly costing six hundred euros each. Costume prices are also inflated twofold. For instance, the artistic-production department recently refused to sew a costume for a singer because it was too expensive, ten thousand dollars. Probably, it was made of platinum. It's a kingdom of mutual back-scratching."

During the trial of the accused in the attack, Sergey Filin stated that artists tried to bribe him, but he always refused. My source refutes this: "He has a terrible reputation. He is greedy and mercenary; if he sees ten cents under a bench, he won't hesitate to reach for them. He had a fund into which artists contributed money to be cast in good roles. Some ballerinas have wealthy husbands, and they are ready to pay for it because roles are status."

Meanwhile, ordinary theater employees and artists complain about low salaries. "An administrative salary of 500-700 dollars is considered normal," asserts a theater administration source. "The ballet corps de ballet has the heaviest load because they participate in every performance. If you're placed in the first line and get to all the tours, you can make a thousand to fifteen hundred dollars a month, but it's grueling work." An employee from the artistic production part says the average salary in their departments is 600-700 dollars: "We constantly write letters to the management asking to revise the wage system. But no one wants to listen."

III. Claqueurs, Destroying Careers

Ballet dancer Igor Tsvirko would like to be remembered by humanity but is not sure he's ready to pay the price for eternity. He knows that almost all great artists die lonely and unhappy - Freddie Mercury, Michael Jackson, Amy Winehouse, Rudolf Nureyev. He danced the latter in a production by the famous and disgraced director Kirill Serebrennikov, who was persecuted by Putin's regime for his activities and forced to leave Russia after a trial. The "gigantic" production, as the press called it, had a complicated fate: the premiere scheduled for summer 2017 was canceled by the theater's management, the director was arrested, and the premiere show with 200 artists was prepared in 11 rehearsal days, ending with a 15-minute standing ovation from the audience. Tsvirko says he pieced together his Nureyev's image bit by bit - reading books, studying photo albums, and archival interviews:

"I saw a deeply lonely person, a fanatic of his craft, who tried not only to be the best in his profession but to become great and did everything to be remembered as a devil in dance. For me, he's an example of terrifying, deadly professionalism - he never cut himself slack, performed around 315 shows a year. He's the only ballet artist who managed to afford an island, where, unfortunately, he remained alone due to his complex, indomitable character, unbridled power of emotions."

Tsvirko speculates that Nureyev-Mercury-Jackson had to pay an unimaginable price for their gift and audience frenzy. However, they say that frenzy sometimes comes much cheaper - you can spend the claque, one of the least studied groups in the Bolshoi Theatre, operating for many decades. This organized group of hired applauders creates artificial success, demand, or, conversely, the failure of entire productions and individual artists. There are terrifying legends about them: they can elevate the needed artist or destroy the career of an undesirable ballerina.

In January 2019, Igor Tsvirko and his wife, ballerina Evgenia Savarskaya, were returning to the Bolshoi Theatre after half a year of living in Budapest. The couple moved to work at the Hungarian Opera House but realized they couldn't stand the new way of life, the unfamiliar organization of work processes, and the separation from their 9-year-old son Lev, who had to be left in Moscow. "The main motivation for our departure was fatigue from routine when it seems that the best solution is to try to change something," explains the artist. "But time passes, and you realize that without your home - and the Bolshoi has become an integral part of my life - it's hard." Igor Tsvirko considers himself a solid craftsman and workaholic - in 2007, after graduating from the Moscow State Academy of Choreography, he joined the Bolshoi Theatre's corps de ballet, and not many career successes were predicted. But Tsvirko is a stubborn, meticulous person who always tries to deliver more than expected. In 2009, young Tsvirko learned 15 minutes before the show that he urgently needed to perform a solo part in "The Golden Age"; in 2016, he almost accidentally played Count Albert in "Giselle" by the great and fearsome ballet patriarch Yuri Grigorovich. He says Luck plays a big part in his profession, as the theater is "quite a complicated thing."

And the Bolshoi's audience, says Tsvirko, is very specific and different from other world theaters. "Hungarians, Italians, Germans," he says, "don't skimp on applause and can even stomp their feet; until recently, audiences in China could loudly eat in the hall during performances and applaud little; in the USA, Russian ballet artists are loved and loudly welcomed; but in Moscow, the audience can remain indifferent even to a high-quality production."

"An artist, when dancing, doesn't look into faces. He can't afford it because he's constantly moving," explains Tsvirko. "If an artist follows the so-called Stanislavski's method, then he should imagine a non-existent fourth wall, not flirt with the audience, but live the story of his character. And the only way to determine the audience's reaction is through applause. Sometimes, where they should clap, the audience doesn't, and you think: something went wrong! But then witnesses tell you that some moment was so mesmerizing that the hall was just in awe - that happens too. Sometimes, if a ballet consists of three acts, in the first, you feel that the audience hasn't woken up yet. This often happens at morning shows. The artist's task then is to engage even more of his reserves to draw the audience into this story, to awaken them. You need to add fire and turn the tide of the meeting. Then the audience rewards with applause!"

This is where the claqueurs come into play, who organizedly attend performances at the invitation of artists. Their leader - an elderly and businesslike man - seats everyone in the hall, and they all know what to do next. They must clap in unison at the right or, conversely, at the wrong moments, can shout "bravo" or "shame," can set the pace, stir up the hall, and throw off the rhythm of both the audience and the artists. Igor Tsvirko says that the artist always precisely knows when a claqueur is applauding - their applause is thunderous: "Claqueurs always clap too deliberately. Sometimes it's annoying because it seems everything has ended, the emotional surge has ebbed - but they continue to applaud, thereby stirring up the audience, provoking it to further applause." But is that bad? "It turns out to be a kind of hype: they create an artificial environment for perceiving an artist or a performance," says the dancer.

"Claque has always existed, in all times," assures Vadim Zhuravlev, the former head of the planning department of the opera part of the Bolshoi Theatre. Now, Vadim runs a famous ballet and opera channel, "Twilight of the Gods," on YouTube and sees himself as a kind of opposition to all the current theatrical-ballet authorities: he criticizes, analyzes, and dissects. "Throughout the world, claque as a class began to disappear. It's a relic of the 19th century. What is it based on? On someone paying for applause. But today, paying for them is silly. Why such a service, say, to artists of Covent Garden? People who buy tickets for 400 pounds clap with full force, sincerely. But this relic has been preserved in the Bolshoi Theatre," explains Zhuravlev. "Sometimes too young artists appear on stage, and these people support them. Although they often deserve applause on their own, the task of claqueurs is to give the newcomer more status," explains Tsvirko. "They can appear to cheer up young or support already experienced artists who suddenly found it very necessary. Of course, the enthusiasm of the audience and the public affects the management's opinion on some issues. At premieres, they can create a certain precedent - either praise an artist, that is, shout 'bravo' to him, or ignore performances with a certain artist. In Soviet times, funeral wreaths and tomatoes were thrown on stage."

Vadim Zhuravlev, who worked in the theater from 2002 to 2009, says that the issue of stopping the claque's activities was raised during his time: "You know who was the first to resist this? People's Artists of the USSR. They said - no, it's impossible, these are very good people, they do the right things. The audience is stupid; it doesn't know where to clap, where to be silent, and where to join in, so these are vital people who do an essential job."

Igor Tsvirko sees the principal value of the theater in that each performance will never be repeated - it exists only here and now. "And if you messed up on stage, then you will no longer have a second chance to fix something," he says. Therefore, proper support is essential to an artist - without applause and flowers, he will completely sink into uncertainty. And as for eternity, Tsvirko will try to get into it, but definitely - without fake applause.

IV. Tsiskaridze and His Ambitions

On the evening of July 3, 2013, in a museum courtyard in the center of Moscow, the former Bolshoi premier Nikolai Tsiskaridze, who had been out of the theater for three days, held a creative meeting with fans. Sweating from ecstasy and heat, around three to four hundred refined ladies and older women stormed the museum. Organizers placed Tsiskaridze on a small wooden stage surrounded by ferns and a sparse tree and handed him a microphone, but the dancer did not sit down, and the chair quickly got buried under lush bouquets, plush toys, and other gifts. Enraptured fans greeted the artist with ovations, sent him air kisses and notes, filmed on iPads like a true rock star, and had him sign everything at hand, even photocopies of saints' likenesses with prayers.

Dressed in white rhinestone-studded pants, Tsiskaridze spent an hour and a half answering the strangest questions: "How do you like Paris?", "How is your kitty doing?" "Can you do a fouetté?" The only topic he avoided was the Bolshoi Theatre. Usually, an artist who creates the effect of a flashbang, Tsiskaridze, kept an unusual silence. He merely mentioned that the theater stands on the site of a plague cemetery, so what else can you expect from it?

Tsiskaridze never hid his dissatisfaction with the theater's management and his desire to take leadership, openly stating, "The Bolshoi Theatre is me." He seized every opportunity to stir up a storm in the media: he was being squeezed, not allowed to dance, mistreated, and meetings were held against him. Tsiskaridze is related to almost any significant scandal at the Bolshoi.

For four years, from 2004 to 2008, when choreographer Alexei Ratmansky led the ballet company, Tsiskaridze was at the forefront of those dissatisfied with the leadership and waged a "holy war" against him. Critics call Ratmansky's period golden, yet the former artistic director is still remembered with disdain in the theater. Ratmansky, democratic and influenced by his work in the West, introduced foreign elements into the company's routine and did not play according to the internal military order, which led to his sabotage by the company. Leading soloists did not recognize him as a leader, teachers scoffed at his initiatives, and dancers refused to perform under various pretexts. "Alexei introduced workshops, for example, thinking he invented the wheel," laughs Boris Akimov today. "But he didn't invent anything; it was invented long before he performed as a boy, and I was already working. We had unscheduled Komsomol-youth performances back in the day, and he comes in thinking no one knows about it." Essentially, there was a "disconnect" between the company and Ratmansky.

Ratmansky resigned and left the country, reportedly with Tsiskaridze's efforts. The dancer then fought for a leadership position: general director, artistic director, or music director. According to numerous sources, he was patronized by the head of "Rostec" Sergey Chemezov, his wife Ekaterina, billionaire Rashid Sardarov, and his wife Marianna, but Tsiskaridze denies all this. However, he did not achieve the position: after Ratmansky, ballet reconstructionist Yuri Burlaka became the artistic director, and by the time his contract ended in March 2011, another battle for the creative director position ensued. Anatoly Iksanov spent a year negotiating with the former head of the Mariinsky Theatre's ballet company and La Scala's principal ballet master, Makhar Vaziev. Vaziev was expected in Moscow and was about to be accommodated in a hotel, but at the last moment, he declined. The backup option was then ballet company manager Gennady Yanin. Still, he quickly fell off the radar: rumors spread that he could be promoted to artistic director, and on March 8, 2011, a website appeared with 182 gay pornographic photos featuring Yanin. The link was emailed to thousands of global theater figures. Yanin was forced to leave the theater, and Iksanov urgently had to look for an artistic director. Lacking other options, he turned to former Bolshoi dancer Sergei Filin, who had been managing the ballet company of the Stanislavski and Nemirovich-Danchenko Musical Theatre (also known as "Stasik") for three years by then. Iksanov gave Filin three days to decide, and Filin quickly agreed to return to his home theater.

It's unclear when the relationship between Tsiskaridze and Filin, who once exchanged compliments, now referring to each other in the press only as "this person," soured. After Filin's appointment, he stated he wanted to make Tsiskaridze the principal ballet teacher because, "unfortunately for Nikolai Tsiskaridze, the position of artistic director has already been occupied for five years." The initiative was somehow shelved, and Tsiskaridze took every opportunity to argue with Filin and accused him of hindering his career or the careers of his students, Denis Rodkin and Angelina Vorontsova. Filin also had complicated relations with Vorontsova. Once, he facilitated her move from Voronezh immediately after finishing school, provided her and her mother with housing, and waited for her to work in "Stasik." Still, the girl changed her mind and went to the Bolshoi Theatre. Vorontsova insists that as soon as Filin returned to the Bolshoi, he held her back, removed her from tours, and did not give her the role of Odette-Odile in "Swan Lake."

Then, in the fall of 2011, there was a scandal with the reconstruction of the historic building: Tsiskaridze called it vandalism and claimed that the stucco was replaced with papier-mâché, instead of gilding, there was gold paint, the acoustics were terrible, some rehearsal rooms had such low ceilings that lifting a ballerina was impossible, there were no windows in the makeup rooms, and the corridors were slippery. The Bolshoi's management denied all accusations.

"Everything Tsiskaridze says is the pure truth," says a staff member of the artistic-production part. "At the grand opening, we worked under emergency conditions because the stage was officially supposed to be handed over a month later. Backdrops and curtains were falling. They wanted to make chandeliers from crystal but made them from Chinese plastic. Plaster falls off in chunks, although the overall picture is okay. Mirrors are crooked, ventilation didn't work, we went to work in winter coats over summer t-shirts and pants. There's nothing to breathe, air conditioners still work like fans, but don't circulate air. They did what the money was enough for because they stole absolutely everything, even cement."

When Anatoly Iksanov's contract was ending, Tsiskaridze wrote a letter to Vladimir Putin and collected signatures from twelve prominent figures in the arts, supporting his candidacy for the position of general director. This also ended in scandal; the contract was extended to Iksanov until 2014 by the Minister of Culture Vladimir Medinsky, who also dismissed him; some cultural figures apologized to Iksanov. Tsiskaridze didn't get what he wanted again and became the main newsmaker for a year after the attack on Filin: the public and the media suspected him of the attack, and Iksanov accused him of involvement in the porn attack on Yanin. Iksanov also accused Tsiskaridze of poisoning the atmosphere in the theater, and Filin told investigators that Tsiskaridze blackmailed him. Tsiskaridze sued the theater against disciplinary reprimands and said that Filin was simulating severe damage from the assassination attempt.

Bolshoi's staff say that Anatoly Iksanov was removed "for a combination of crimes": for a year of scandals, for the offended ballerina Svetlana Zakharova, and for the dismissal of Tsiskaridze, behind whom influential patrons stood. Tsiskaridze himself was scandalously appointed as the acting rector of the Vaganova Academy of Russian Ballet in Saint Petersburg in late October after lengthy negotiations and reshuffles. As ballet master-teacher Valery Lagunov writes in his memoirs, Tsiskaridze, although "often looks unattractive as a person," pleases with his battles: "He almost always wins."

V. Dmitrichenko, the Union, and Money

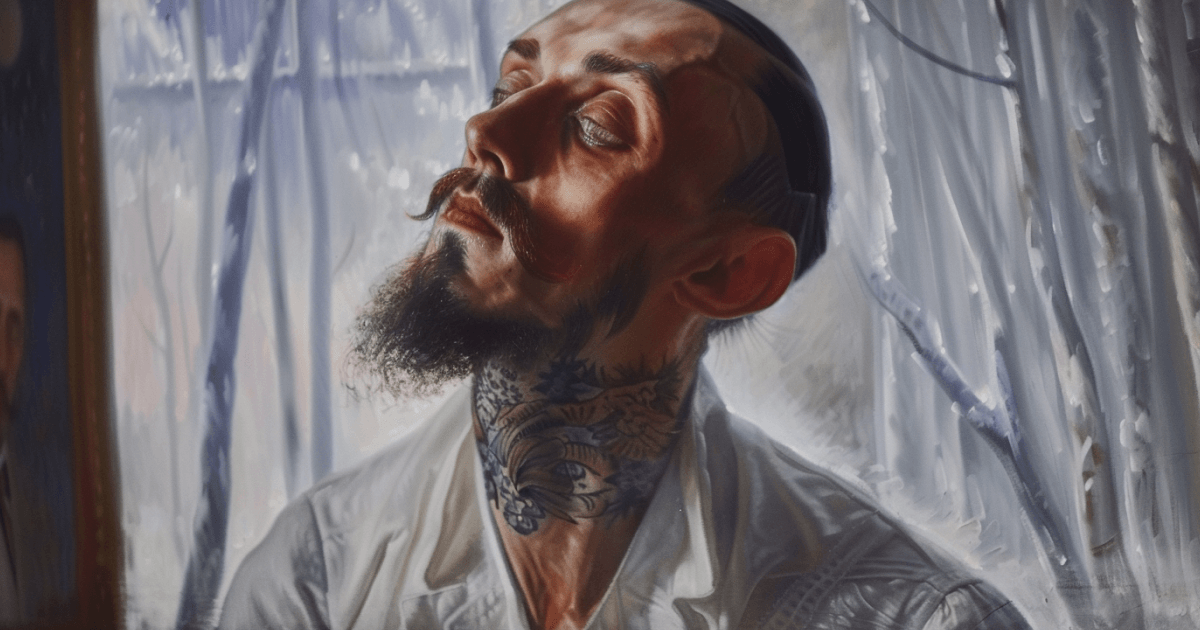

On the afternoon of August 26, 2013, the Moscow City Court considered another appeal to extend the arrest of the Bolshoi's leading soloist, Pavel Dmitrichenko. The soloist is shown from the detention center on a plasma screen suspended from the ceiling: pale, standing with his back to the wall, looking sideways. "I've already sat enough, thank you," he says in response to the judge's offer to sit down. At the beginning of August, Dmitrichenko changed his lawyer again, along with his rhetoric: for the first time, the soloist apologized to Filin for the attack and said their conflict was within the creative process, which is expected since not only he had complaints against the artistic director. Wished Filin a speedy recovery, declared his innocence and willingness to compensate for any damage, and asked for reconciliation. Today, he repeats the same in general terms, doesn't say anything extra, and agrees with his lawyer. But all year before this, he didn't hold back in words - admitted to organizing the attack (but not in choosing the method of execution; wanted just to beat up) and consistently made a whole bunch of accusations against Filin: distribution of grants in his interests, deprivation of artists of their due bonuses, threats, insults and bringing theater women to tears, removing people, including himself and his civil wife Angelina Vorontsova, from the creative process.

Dmitrichenko is somewhat of a punk dancer. Wild, audacious, sharply quick: tough character, straightforward communication style, and, quite untypical for ballet dancers, tattoos. Iksanov said Dmitrichenko was naturally unbalanced, naive, and impulsive: "Lights up like a match and extinguishes just as fast." Right after the arrest, three hundred Bolshoi employees signed a collective letter in defense of Dmitrichenko, and many in the theater still do not believe he ordered the crime and consider him slandered. "If something didn't suit Pasha Dmitrichenko, he would gather the company, call Filin, and punch him in front of everyone. That would be Pasha," says a staff member of the artistic department. Dmitrichenko is the opposite of Sergei Filin: the former is a blond, the latter a brunette, the former can't wait to lose his temper in public, and the latter keeps himself in check. However, they share one trait they might not notice in each other: caring for their close circle. But this is where all the conflicts stem from - the circles are different.

According to stories, the company was glad when Sergei Filin was appointed artistic director: one of their own, familiar with the company's problems. But the joy quickly faded. First, Filin brought his entire team from "Stasik": adviser Dilyara Timerkazina, an assistant, a ballet inspector, a repertoire and cast assistant, and three dancers. The newcomers quickly climbed the career ladder, annoying colleagues, and the adviser and assistant, according to numerous accounts, interfered in the creative process, annoying the artists even more. Secondly, there was no expansion of the staffing schedule for Filin's administrative team, so some veterans had to lose their jobs. For example, Filin tried to remove the head of the ballet office, Veronika Sanadze, but Pavel Dmitrichenko and the company stood up for her. They saved Sanadze, but after that, Filin and the artists had more and more quarrels. Nine months after Filin's arrival, a star pair of dancers, Ivan Vasiliev and Natalia Osipova, fled the theater.

Filin assures there was no open conflict between him and Pavel Dmitrichenko; he had no animosity towards him, but the artist, at every opportunity, demonstrated his contempt for him. However, Filin does not consider Dmitrichenko the final customer of the assassination. "Their relations were quite complicated because Dmitrichenko is a truth-seeker, an active union activist, and sat like a thorn in the management's side," says a theater administration source. Besides union activities, Dmitrichenko collected money for artists' treatments and led the "Artists of the Bolshoi Theatre" housing construction cooperative. According to a staff member of the artistic department, he fought most against the management's humiliations of artists, reduced payments, and unpaid overtime. "It's considered normal here that rehearsals last until ten in the evening; then, they offer to stay another half an hour. The orchestra always stands up and leaves at such moments until a document appears stating everything will be paid. But ballet dancers always got shortchanged," asserts the staff member of the artistic department.

The situation with the Bolshoi Theatre's union is curious. In 2006, a new creative union sprouted from the one remaining from Soviet times for, the ballet and opera companies. Sergei Filin became the union's chairman, helped by his old friend, dancer Ruslan Pronin. Filin kept the chairman position when he left for "Stasik" in 2008 and even when he returned to the Bolshoi in 2011. Filin made Pronin his deputy and appointed Gennady Yanin as the manager of the ballet company. Thus, they both managed the company and the union. Until 2013, Filin remained the head of the union because, according to union members, it bothered no one: he did not block financial aid to theater employees and agreed with proposals. But talks about him being unable to simultaneously be the head of the union and the artistic director became more frequent, and the union agreed to re-elect the head. Dmitrichenko led the group that was dissatisfied with Filin's position: How can he resolve union issues as the artistic director? The re-election was scheduled for this January but was postponed due to the attack on Filin. The first round of voting took place on March 2, with Pavel Dmitrichenko almost unanimously elected. Three days later, he was arrested on charges of organizing an attack on Sergei Filin. The second round of voting took place on March 9. Dmitrichenko was elected head of the union, and in his absence, Ruslan Pronin was made the acting head, once Filin's friend.

It's unknown precisely what the old friends fell out over, but it's known that Pronin was mentioned in Filin's correspondence, which was hacked and published online shortly before the attack. "He turned out to be a dark figure pulling the blanket over himself, not covering me but, on the contrary, only fanning the flames. In December, I will remove him and appoint Sasha Vetrov, I think, for now!" Filin wrote (he insists that the letters are only half genuine: some parts were added by hackers). Request on the day of the attack, Ruslan Pronin, at Dmitrichenko's request, clarified Filin's plans for the evening, making him one of the initial suspects. A little later, he wrote complaints to the theater's administration about Tsiskaridze's interviews, for which the soloist received one of the reprimands they tried to use to fire him. In April, Pronin visited Dmitrichenko's trial, signed a surety, actively supported the leading soloist, and passed greetings from Angelina Vorontsova. Five days later, Pronin was notified that his employment contract was terminated. Now, he rarely visits Russia, and according to rumors, he is banned from the theater. Yet, he remains the acting head of the union.

"When Dmitry Medvedev said the crime must be solved, the police started floundering, and the circle of suspects narrowed to three people – Dmitrichenko, Pronin, and Tsiskaridze," assures our source in the theater's leadership. "They took the trail and, through simple combinations, decided as follows: Pronin is Filin's former buddy, he knows too much about him, he should not be touched; Tsiskaridze is a media personality and trades his face everywhere, but Dmitrichenko can be taken."

As the judge leaves to decide on Dmitrichenko's appeal, his relatives line up under the plasma and show Pavel signs with a message: "We love, everything is fine with us, hold on there." Angelina Vorontsova is not in the hall. "How thin and green he is," parents discuss in horror. "Yeah, just a bad hotel," Dmitrichenko jokes, leaning his head against the grate. Grates, he claims, don't scare him: "The Count of Monte Cristo sat for twenty years and nothing."

VI. Blind Fate of Art

Talking about the attack on Sergei Filin in the theater is not favored, as if it's something indecent, and people turn up their noses when you bring it up. All theater employees condemn the attack as "airing dirty laundry" and genuinely get offended and irritated when the media reports on it: the constant discussion of the topic damages the prestige and image of the theater, a symbol of the country. Paradoxically, the idea that the artists themselves damage the image doesn't seem to occur to anyone. At some point, it may seem that the assault on the night of January 18, 2013, is no more a misunderstanding than if a stage beam had simply fallen on Sergei Filin backstage. It's unfortunate, of course, but we put on the best ballet performances in the world, and we are so beautiful and diligent.

Alexei Ratmansky described the reasons for the attack in a Facebook post: there's no theater ethics in the theater, but a flourishing disgusting claque, ticket speculators, half-crazy fans "ready to slit the throats of their idols' rivals," lies in the press, and scandalous interviews by employees. If you add to this the fact that, according to ballet dancers, there are no people more obsessed with sex than ballet dancers themselves, and Sergei Filin, who has been married three times to women from the troupe, incredibly loves women, which he never hid, then a thunderously explosive picture emerges.

But the thing is, the intensity of passions in the Bolshoi Theater has always been the same; we just didn't know about it or didn't pay attention. Take Yuri Grigorovich, who managed the theater for thirty-one years. He is still called the Stalin of domestic ballet: a merciless dictator, who burnt out enemies, eradicated dissent, expelled entire ballet families. Under Grigorovich, denunciations were also a form of entertainment, Grigorovich also sidelined the displeased, also promoted favorites, also, according to rumors, slept with all the women in the troupe, also harshly punished everyone who worked with his sworn enemy, Maya Plisetskaya. The scale of repression and scandals was no less than today's: Grigorovich fought with the theater director, meetings were held at rehearsals, artists went on strike right during performances, the union went on strike, and in 1995 Grigorovich was indeed expelled from the theater. But they didn't throw acid at him.

Therefore, a plethora of questions remain about this terrible tangle. However, it's clear: a lifetime wouldn't be enough to untangle the intrigues of the Bolshoi and find out how deep the rabbit hole goes. Even within the theater itself, no one knows the full scale of what's happening within its walls, as Boris Akimov believes. However, some questions would be easier to answer if they weren't shrouded in a veil of mystery. While preparing this text, the number of refusals to speak exceeded all conceivable norms.

Countless ballerinas, ballet dancers, and mime artists don't want to communicate for fear of being punished or fired later – item 74 of the internal labor order prohibits providing negative information to the media. Gennady Yanin, the first confirmed victim of the Bolshoi, refused to speak twice: "I will not tell the truth, and it's too late for nonsense. We never aired dirty laundry. After all, Putin probably argued with his wife too, but why talk about it?" Ballet master Yuri Grigorovich refused to speak, citing illness and a busy schedule. The leading ballet critic and historian of Russian ballet, Vadim Gaevsky, who was banned from publication in the USSR for criticizing Grigorovich, doesn't want to talk because he's old and would instead work. Renowned ballet critic Tatyana Kuznetsova said she would only speak for 300 euros. The head of the claque, Roman Abramov, said he wanted nothing to do with journalists and suggested they write about how great the Bolshoi is instead. Dmitrichenko's lawyer, Sergei Kadyrov, indignantly refused to pass written questions to his client in jail: "Do I look like a pigeon? There's no such norm in the criminal procedure code. You're inciting a person to illegal actions!" The previous lawyer of the attack executor, Yuri Zarutsky, Nikolai Polozov, passed questions to his client, who even answered them. Still, it was impossible to retrieve them – Polozov was removed from the case. The new lawyer, Sergei Kupriyanov, assured Zarutsky that he had changed his mind about passing the answers: "After all, he should learn something too." Ruslan Pronin, one of the most mysterious figures in this story, agreed to an interview and postponed the conversation for five months under various pretexts. Eventually, even Sergei Filin refused, saying he currently has no time. Filin's assistant, Dilyara Timerzhanina, also declined an interview, noting that dirty laundry should not have been aired and that it's better to start with oneself.

Bolshoi workers claim that all problems in the "friendly troupe" come from a group of troublemakers who took internal disputes to a new level contrary to all theater norms. They believe such incidents will not happen again. Moreover, many in the Bolshoi do not doubt that Dmitrichenko indeed wanted only to have Filin beaten up, and Yuri Zarutsky himself introduced the acid. Following this logic, the attack on Filin is merely a fate, an accident that spiraled out of control as if art itself attacked him. Thus, it could have happened anytime and to anyone in the theater. After all, Sergei Filin is no better than others in the Bolshoi Theater – they are all cut from the same cloth. It just needed a spark for everything to explode into hell and for heads to fly. After all, madness, as the Joker said, is like gravity – all it takes is a little push.

It's evening, and it's snowing. A high-ranking State Academic Bolshoi Theater employee is returning home after a performance. He parks his car and heads to the entrance of his building. It's 23:07 on the clock. For the last couple of weeks, someone has been making his life difficult: deflating tires, hacking his mail, posting correspondences online, and blocking his phone with endless auto-dialing. Now, even if the code lock on the entrance gate is malfunctioning, the keys won't work. While the Bolshoi employee is trying to figure out the intercom, someone approaches him from behind and calls out his name.

The curtain rises.

1. Transform your identity crisis and own your story with an online narrative therapy session. Reduce anxiety and discover new perspectives through these collaborative conversations

2. Turn your life experience and passion into captivating media products with step-by-step coaching. I will guide you from ideation to creation, and together we'll craft your dream project

If you have any questions, feel free to reach me at most@hey.com