Russian Rookie's Failed Quest to Win the Indy500 Race

For decades, Mikhail Aleshin tried to break into Formula 1. Instead, he became the first-ever Russian driver in the iconic American race, which changed his life

At fourteen, he became the youngest participant in Formula 3 and was supposed to become the first Russian in Formula 1, but this dream never came true. In 2013, race car driver Mikhail Aleshin faced failure and moved to the USA to continue his career. There, Aleshin became the first Russian to enter the iconic American IndyCar races, showing decent results and reevaluating much about his own life. However, his first race in Indianapolis in May 2014 ended in defeat, bringing him new revelations about himself and the world.

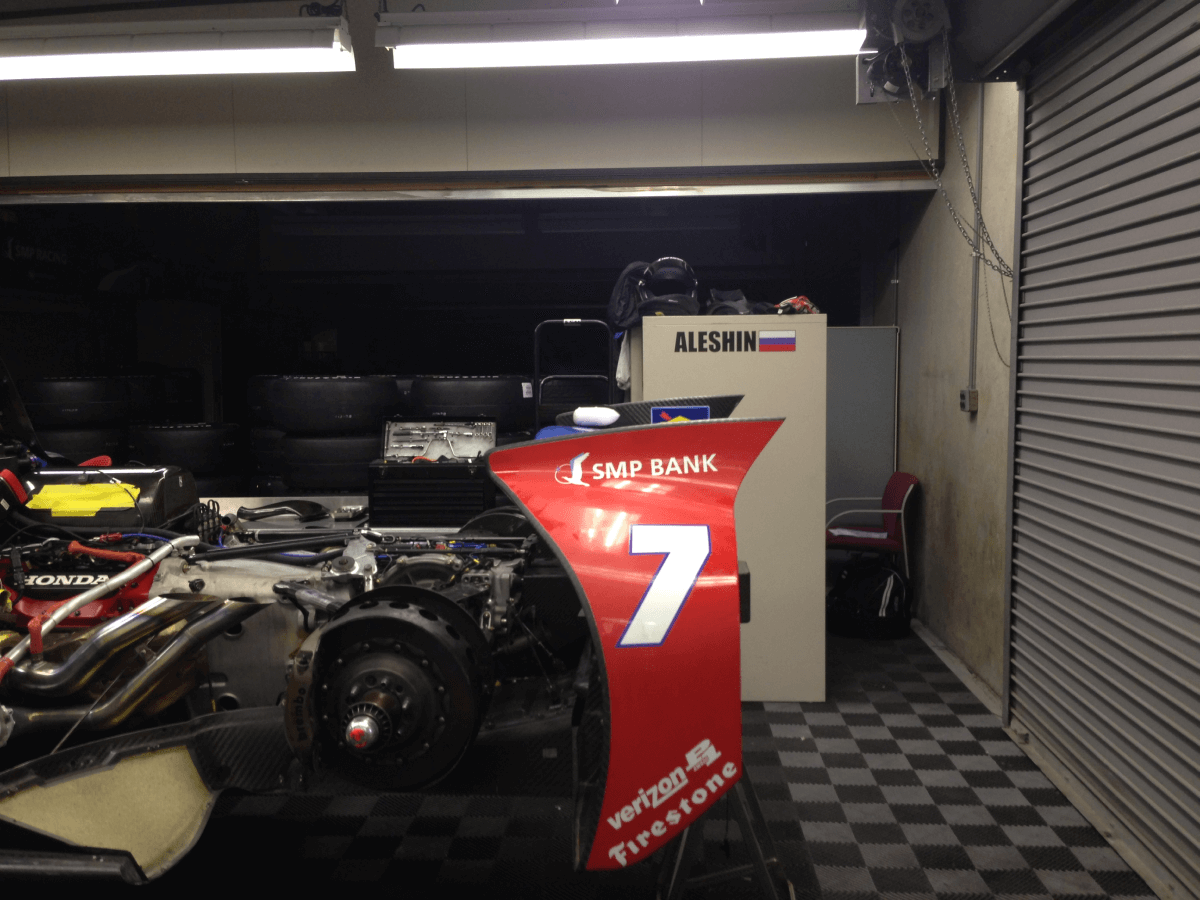

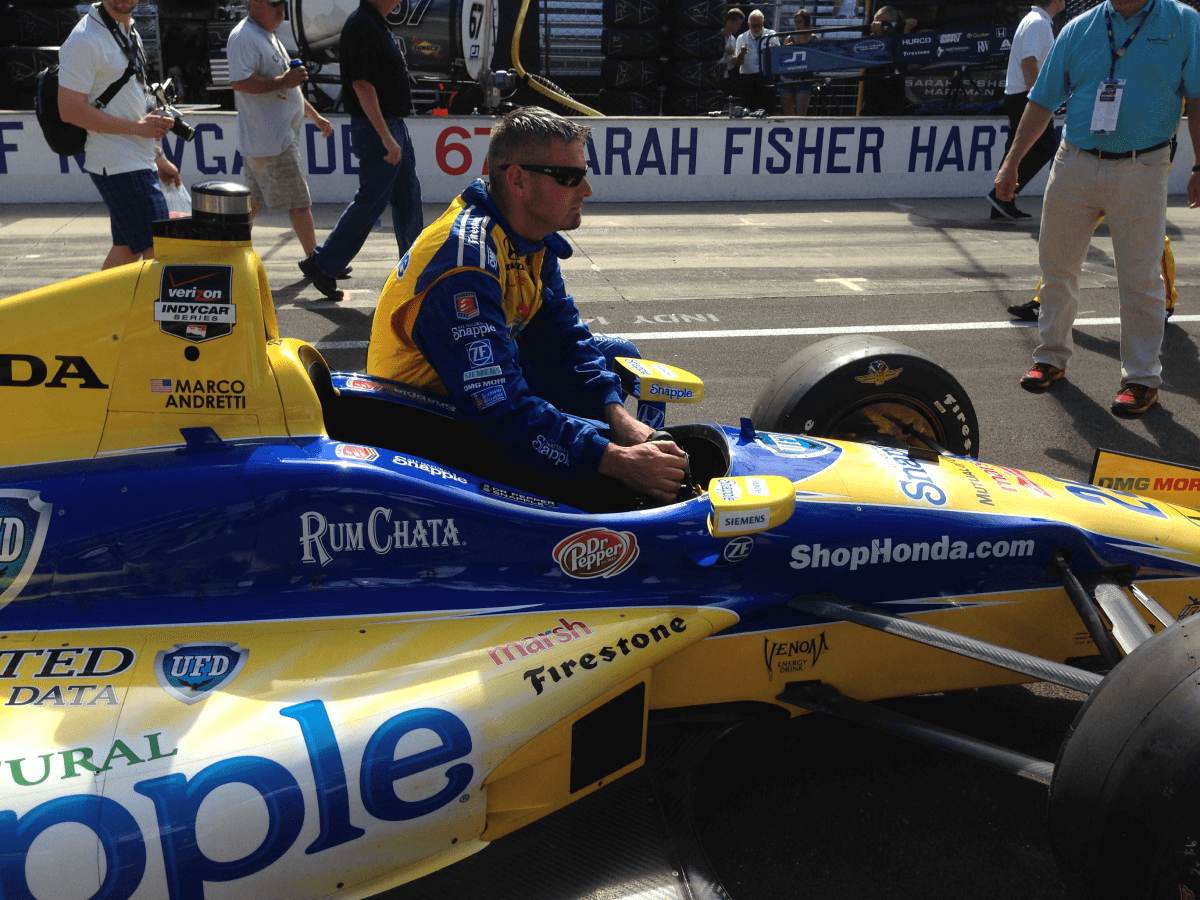

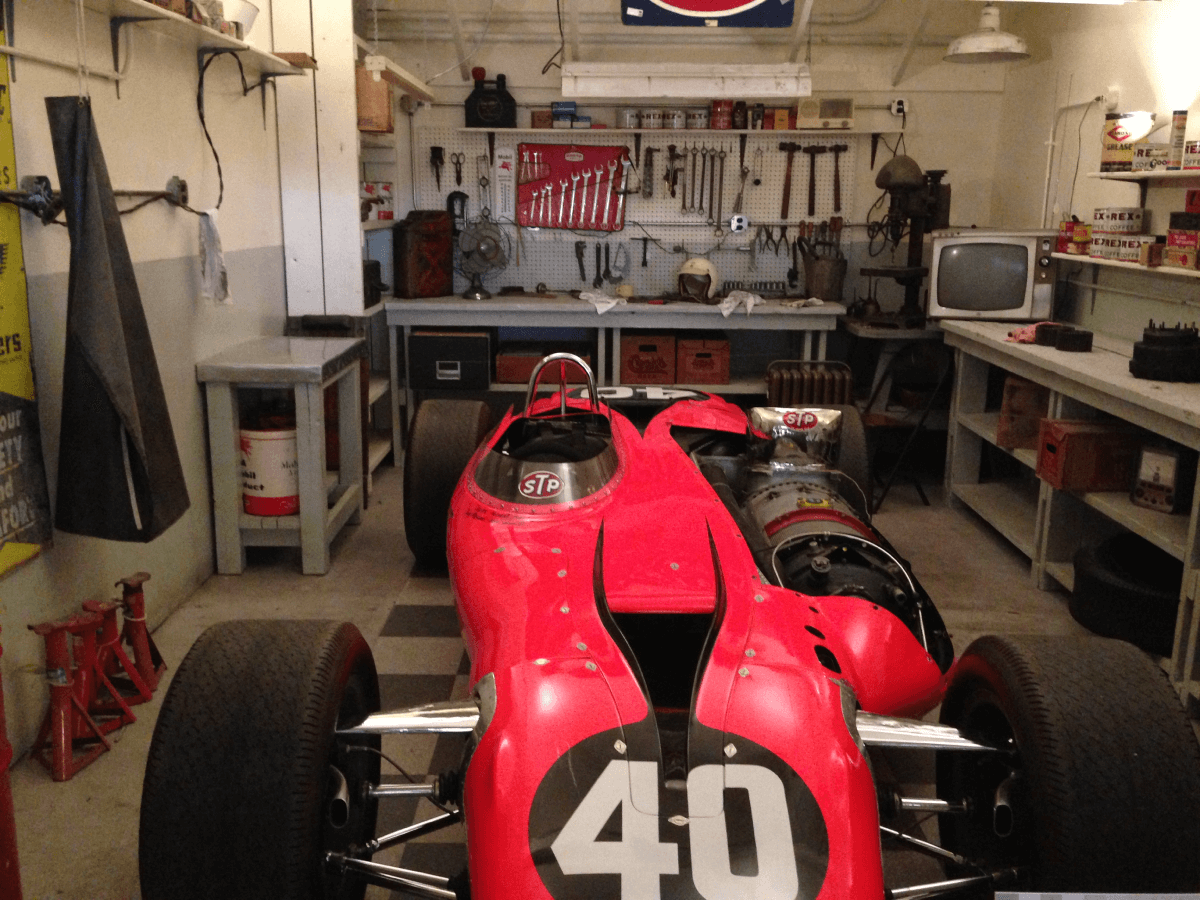

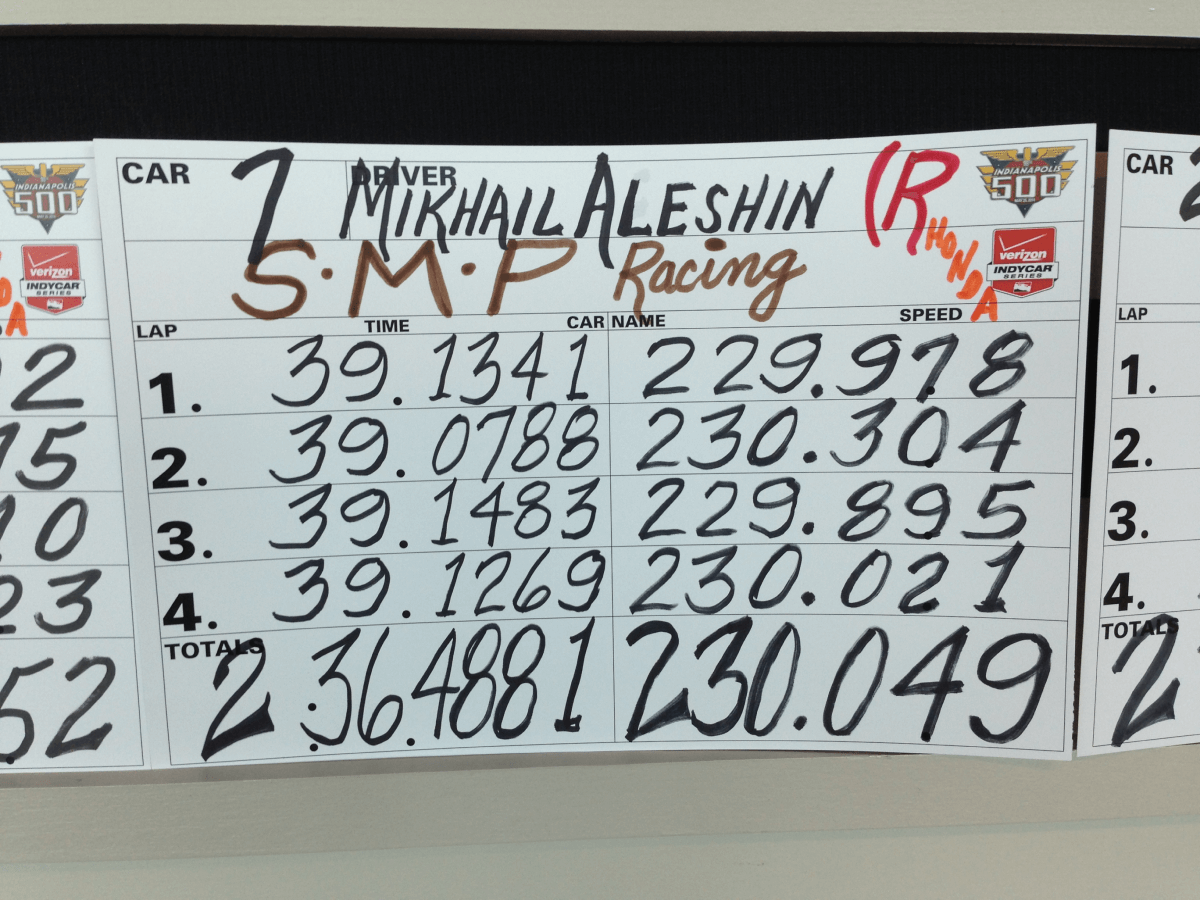

The day before that damned finish line, race car driver Mikhail Aleshin sits in the team garage, cleaning his helmet so meticulously, as if it won't be covered in dust and soot after tomorrow's race, so carefully, as if it's the most critical task in the world. The helmet will never again be coated with bits of sticky burnt rubber. Aleshin folds the microfiber cloth in half, wets it with car wax, and rubs the image of a red Soviet star on the carbon fiber crown repeatedly. Next to the helmet on the table shines a massive silver ring with a blue stone, which was ceremoniously presented to Aleshin and the other thirty-two drivers that morning. A symbol of belonging to a closed caste. Around the blue stone runs the inscription: Indianapolis 500. Below, the driver's name and average speed are engraved in the qualifications. Aleshin's reads — 230.049 miles per hour. Three hundred seventy kilometers and two hundred twenty-seven meters per hour, one and a half times faster than a high-speed train, just over two and a half times slower than a Boeing 737. Aleshin wets the cloth again and diligently polishes the red-blue helmet's dome.

In garage A10-A11, it's deceptively quiet; in the adjacent room, under the steady hum of ceiling fan blades, a mechanic tunes the engine of a disassembled racer, a crowd of gawking journalists mills about. Reluctantly, without letting go of his helmet, Aleshin gives the final interviews before the start. Aleshin turned twenty-seven two days ago in Indianapolis, Indiana, USA, a garage right in the middle of the world's oldest racing track, and tomorrow is the world's leading race. But all Aleshin can think about now is how to find himself alone and go to sleep suddenly. No way. Aleshin unfolds the cloth.

Aleshin has a short, dark mohawk and a quiet, almost shy voice. He constantly looks away from his interlocutor, and he's irritated when something gets out of his control when insurmountable obstacles arise. His aloofness and seeming arrogance sharply contrast with the almost showy sheen of his team's official white shirt. The shirt is embroidered with team logos and sponsors, a high collar, light jeans, and loafers on bare feet — and Aleshin vaguely reminds those guys impersonating Elvis Presley on the streets of Las Vegas. After all, why else would he play the electric guitar in a rock band?

Here, he's viewed as an alien creature. The first Russian participating in the ancient, almost as old as America itself, American race "500 miles of Indianapolis". The local fan community hardly knows anything about him and calls him The Russian. Aleshin is not surprised: they looked at him the same way back in 2000 when he was the first Russian competing in the world karting championship, the same way they looked when he was the first Russian on the threshold of "Formula-1". In the local press, he's described as a modest man with broken but understandable English and impressive results in qualifications, practice laps, and other series races: best speed, best lap time, one of the fastest rookies.

But what's most important now is wherever his name is mentioned in Indianapolis, it's invariably followed by the symbol — "R." Rookie. A newcomer. An athlete who has just moved to the professional league. Here, all his experience and merits have been nullified, ceased to matter, turned into a brief line "participated in competitions in Europe," into dust. Aleshin wipes off the image of a snarling mouse with a purple mohawk and an electric guitar on the back of his helmet. A similar mouse was on one of his first helmets when, in 1996, at the age of nine, he started his long racing journey from professional karting.

Three-time champion of Russia and champion of Scandinavia in karting. At fourteen, he became the youngest participant in Formula 3. And then everywhere — the first Russian, the first Russian, the first Russian. At nineteen, he became the first Russian to win an international open-wheel series race: won the first stage of the World Series by Renault in Monza. Bronze medalist of Formula 2 and the first Russian to receive the FIA Super Licence, which was supposed to allow him to compete in Formula 1. In 2010, he became the first Russian to win the Formula "Renault" 3.5, the last step before "Formula-1". He was on the verge of the Royal races, but could not cross it and become the first Russian in "Formula-1", although he still calls himself the man who paved the way for all the followers. Due to the lack of sponsors, Aleshin endlessly hovered somewhere around "Formula-1": drove a car at auto shows near the Kremlin walls, participated in Renault F1 team tests in Abu Dhabi and Magny-Cours, piloted the car of the main designer in motorsport Adrian Newey in demonstration sessions.

The reality turned out merciless: talent and results without sponsorship money were not enough to touch the Queen of motorsport, the dream. For eight years in a row, Aleshin thought every day that now he would win another race and finally reach the top of the automotive ziggurat. But if he didn't fall lower, he gradually disappeared from view. And almost all this time, the back of his helmet featured a punk mouse.

On average, Aleshin changes two helmets per season, and for many years now, he has been painting them with his Moscow friend, a professional icon restorer. The helmet is covered with several layers of special paint and is resistant to dust, stones, sand, and burnt tires. The helmet with the first mouse was bought in a store, but now Aleshin finds a mouse on the Internet according to his mood, prints out the picture, and the friend-restorer paints it on the back of the helmet. Sometimes, the mouse disappears, but then it always comes back. For Aleshin, it's not superstition; it's just a joke: there were superstitions when he was young, but he decided to eliminate them — only the pleasure of cleaning the helmet yourself before the start remains. The team teases Aleshin's love for personally dealing with the helmet, suggesting he might as well mop the garage floor — after all, a racer of his level shouldn't be doing such things himself.

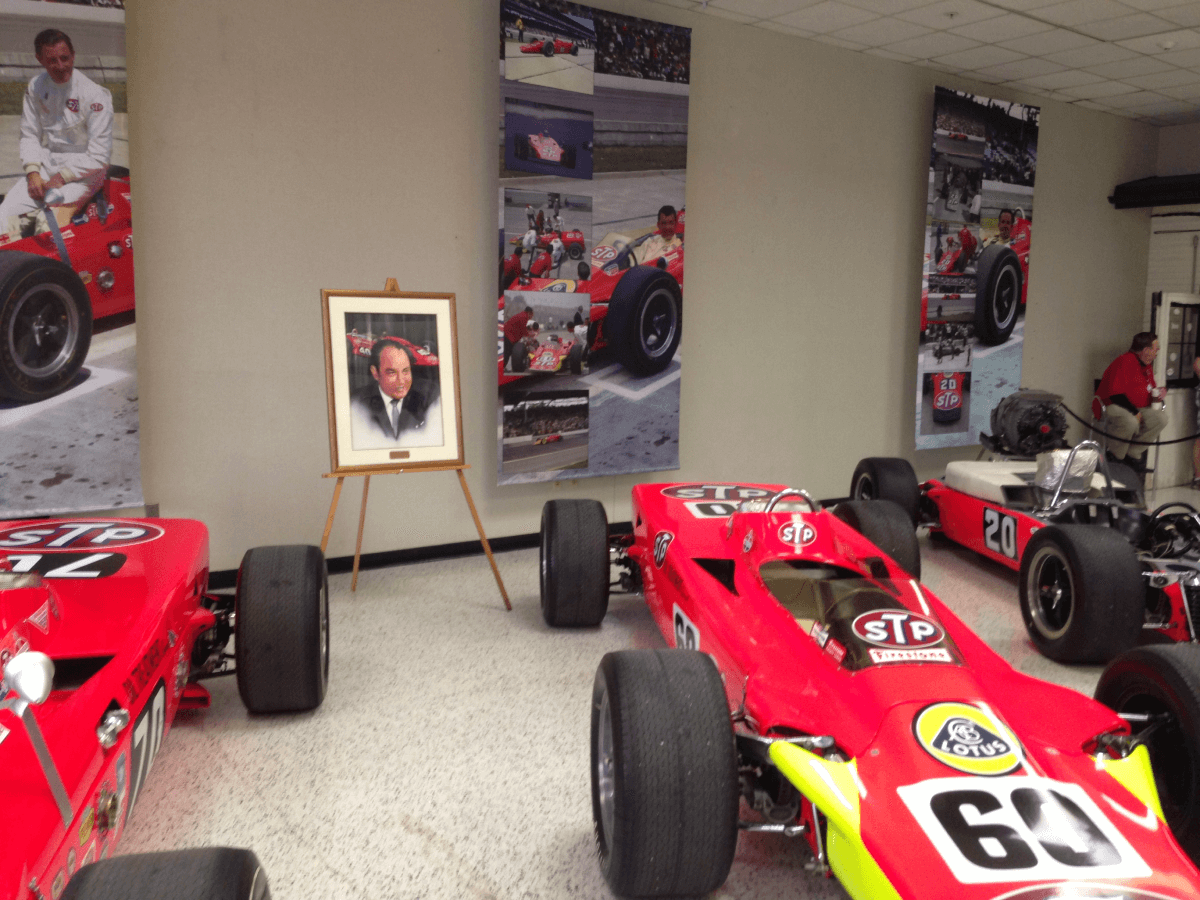

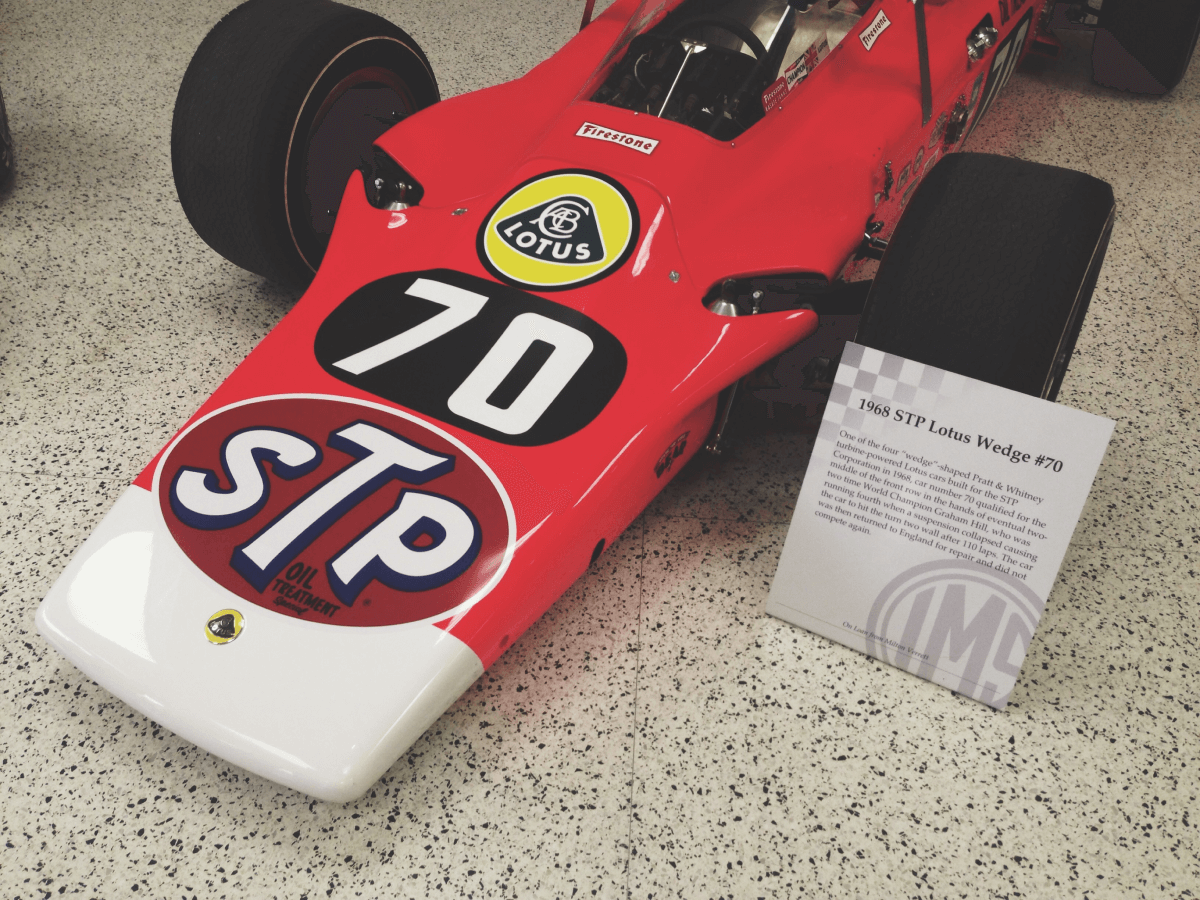

The "500 Miles of Indianapolis" race, or "Indy500", is the American auto racing Olympus, there's nothing higher. Formula 1 is not watched here: why, if there's their own, faster, more aggressive, and more popular? Aleshin somewhat resentfully calls Formula 1 a closed club, where big money decides everything, and it's not always clear what the money is spent on. If Schumacher didn't have sponsors, Aleshin says, no one would have known who Schumacher was. Here, it's different: the team and car are cheaper, and there's no insane spending on racing-related things. Aleshin spent three years looking for ways into Indy500 and, last November, announced that he was moving to the Schmidt Peterson Motorsports team. One of the company's owners, paralyzed former racer Sam Schmidt, asserts that Aleshin will help the team improve, and he's swift to catch on for a newcomer to the States. Teammate Simon Pagenaud is amazed by Aleshin's meticulousness: he constantly studies the results of his and others' races, telemetry, settings, and pilots' feedback and neatly records everything in a notebook. Since January, Aleshin has been living in Indianapolis, renting an apartment, and is happy about the lack of traffic jams and missing home. Initially, there was a feeling of stepping into the unknown, but now that feeling is gone. There's a whole new world here, completely invisible from Russia: Indy500 is much less prevalent in Russia than Formula 1. But now Aleshin understands that in terms of spectacle, power, struggle, and fans, Indy500 is far more interesting than the Royal races. Suddenly, he finally found his place where he had only seen a backup option just a year and a half ago.

Aleshin throws the cloth into the trash can, picks up the gleaming helmet under his arm, and slips the heavy ceremonial ring onto his right finger. The ring seems strange to him; they like such things here, but he can't imagine wearing it back home in Moscow. Aleshin is calm and detached. The ring shines, the red-blue helmet shines, and the shirt shines; in the garage, only the hum of the blades is heard, but outside, under the scorching sun, nervous tension gradually mounts. Aleshin places the helmet on the nameplate locker.

Tomorrow, damn it, is The Race.

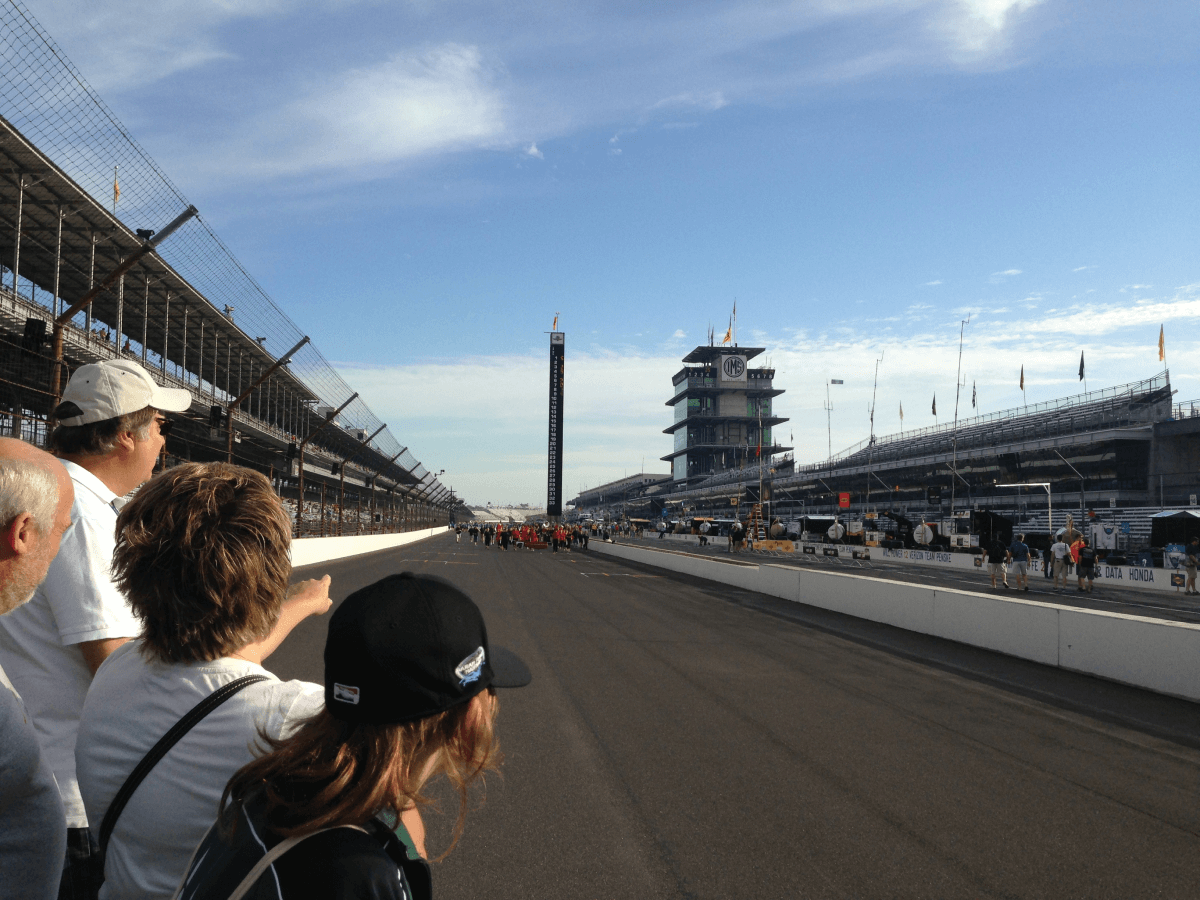

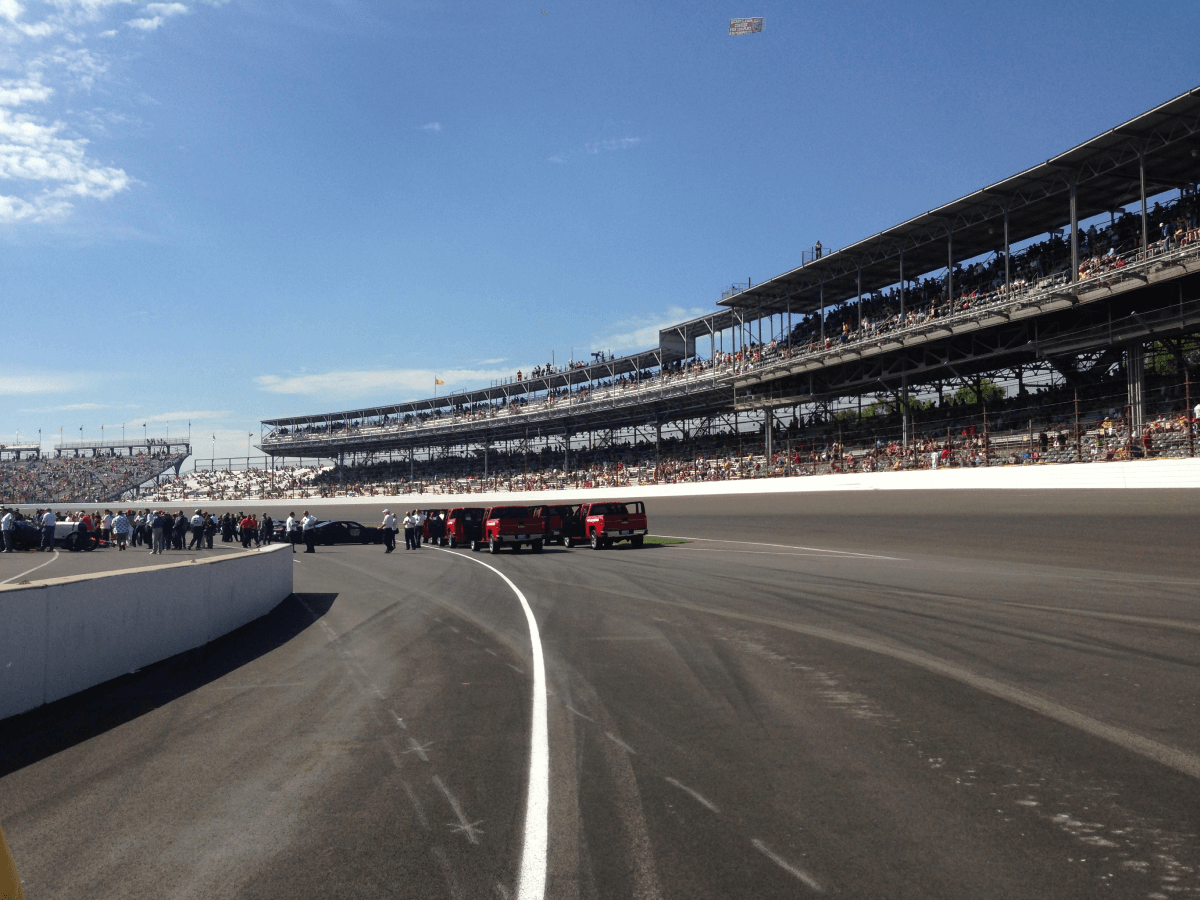

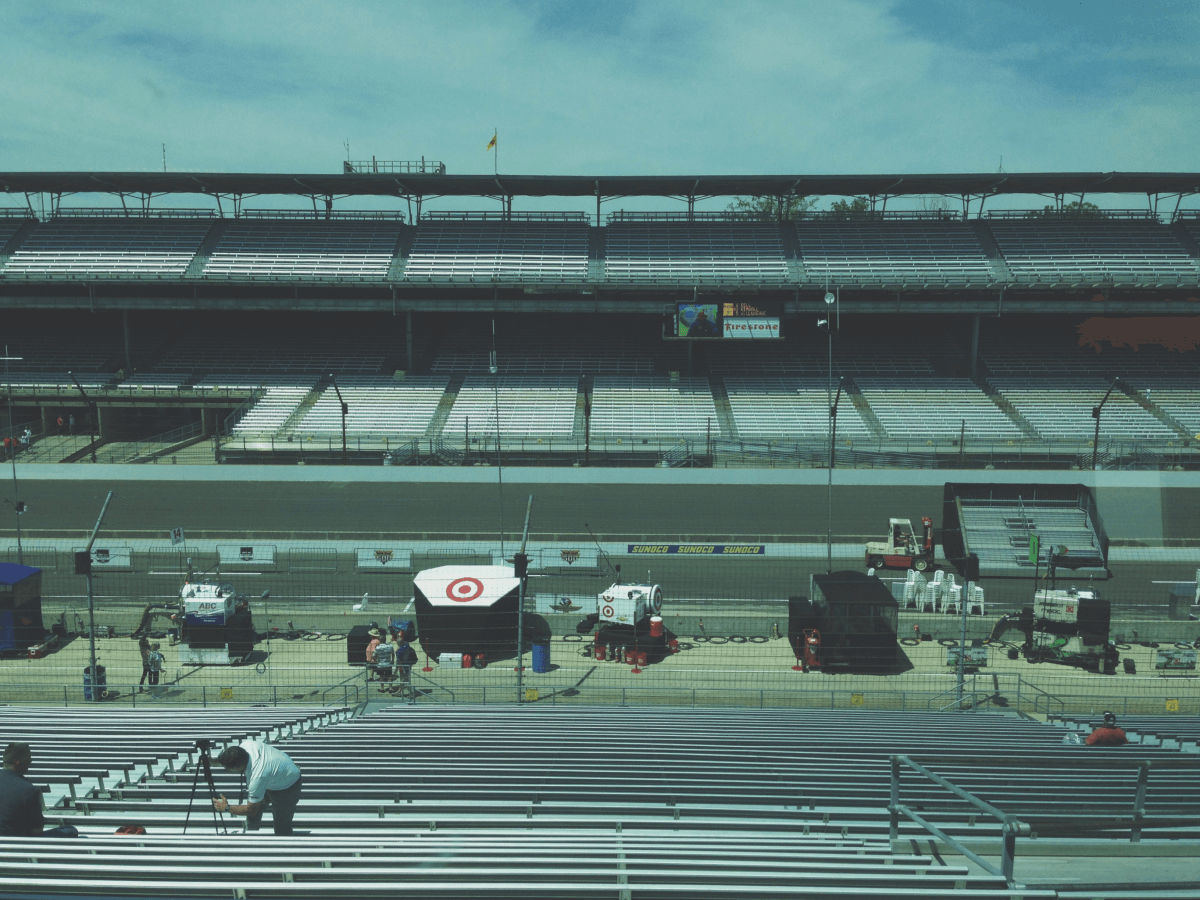

At dawn, the lawns of the one-story houses in the town of Speedway are packed with cars — where a barbecue grill usually stands for Sunday steaks, four or six pickups are squeezed in. The closer to the track, the more expensive the parking: ten, thirty, forty dollars. Speedway is a suburb-enclave of Indianapolis, the automotive Vatican, with twelve square kilometers, a population of just over eleven thousand people, and its police, fire department, and municipal services. The city center, the dominant feature — Indianapolis Motor Speedway, built in 1909, the American racing Olympus. An oval track, over four kilometers long, with four turns, banking at nine degrees, stands for nearly three hundred thousand people. Inside the oval are hills, lakes, garages, parking lots, and a museum. The race will last three hours, 200 laps, 500 miles — 804 kilometers. Glass skyscrapers give way to wooden box-like houses; the road to the track is dotted with fairs of used automotive monsters, gun shops, and strip clubs. A few blocks before the track, police cordons are set up, and heated taxi drivers hurry off to bring more people. Heat. Spectators carry crates of beer and mini-fridges on wheels. "These cars scream piercingly!" shouts a deaf grandpa selling earplugs for two bucks a pack. An FBI van that looks like a mobile ice cream truck is on duty. The crowd merges into an excited roar.

The "500 Miles of Indianapolis" race annually becomes the crown of a whole month of folk festivities, parades, festivals, beauty contests, marathons, qualifications, and meetings with legendary former racers. All May in Indianapolis, the excitement builds up, and by the start of the "Indy500," almost religious ecstasy reaches its peak. The city's population increases by half a million people by one and a half times. At the airport, visitors are greeted by the prehistoric old-timer race car Basement Bessie, which in 1950 was assembled from makeshift means by a local mechanic and racer, then disassembled to be taken out of the basement into the world, reassembled, and raced. Inside the track, a tent city grows; people don't get out of race car simulators, and the Dallara factory that produces car chassis is rented out for private events. The town talks only about race. In the evening, before at Hilton, a minivan stops, and from it tumble local affluent retirees with champagne, laughing. Slender elderly ladies in expensive evening dresses, fat grandpas in red ties with whimsical gold ornaments, and big red hats with gold beads. Red-faced grandpas, barely standing on their feet, greet tourists smoking at the hotel entrance loudly. Learning that the tourists came to the race without their wives, one of the retirees takes off his Masonic hat and, with a severe look, holding onto a friend, declares in a funeral voice:

— My friends, I officially bless you;— tries to make the sign of the cross but fails. — Good luck to you. Seriously, guys, good luck.

Spectators raid the endless souvenir rows, and the entrances inside the track smell of warm beer and, for some reason, shampoo. There are many crazy festivities in the world: the San Fermin festival and running of the bulls in Pamplona, Queen's Day in Amsterdam, and the gay parade in Reykjavik, but they are nothing compared to the racing trance of Indianapolis. People try to break into the racers' garages, even for a moment, until security remarks; without passes, they climb onto the pit lane to look at the cars. Break-dancing and tecktonik. A noisy column of white men in kilts, berets, and bagpipes passes by — why not, after all? On the hills at the fourth turn, barbecues are sizzling. Young guy Douglas in a knitted hat jumps up and sits down on the ground again, shouting:

— What's her name? What do you call her, this bitch?! She sees Russia from her house in Alaska! Sarah motherfucking Palin! Sarah Palin sees all this shit, guys! — Douglas pretends to shoot with an invisible rifle, whether at the invisible Palin or Russia — Bang!

An hour and a half before the start, cutting through the crowd on the pit lane, teams bring out the cars. They place them according to the results of the qualifications, line up helmets on the rear wing, and open umbrellas over the cockpits so the equipment doesn't overheat in the thirty-degree sun. Several hundred people with special passes wander between the cars and discreetly touch the astonishing carbon fiber bodies of the vehicles, surprisingly light for such fire-breathing monsters. People take photos against the backdrop of calm team members and kiss the brick finish line on camera. In the past, the Motor Speedway track was laid out in bricks; then, it was replaced with asphalt, leaving a narrow strip in memory. The track is still called "The Brickyard," but the line remains icy cold in such heat. The white-blue-red "Dallara" No. 7 of Aleshin is moved to the 15th position on the outer radius of the track, then taken away and returned closer to the start.

The start of Indy500 is always a caravan of traditions, eternal, like the competition itself. The honorary delivery of the green start flag. A lap of vintage cars from the museum, as splendid as a gum commercial smile. Introduction of the racers. A small military march. Performance of patriotic songs "America the Beautiful" and "God Bless America," with mandatory joyful cries from the stands at the word "free." The bishop's performance. Ceremonial volleys from rifles. The anthem. The team broadcasts, through megaphones, "Drivers, to your cars." Musician James "Jim" Nabors sings the unofficial anthem of Indiana, "Back Home Again in Indiana," for the forty-second time. The prize trophy shines on the podium — a giant silver vase with the faces of all previous winners of this race engraved on it. Participants of the Miss Indiana contest are present. Traditions! Sitting in the car, Aleshin finds it amusing — it's all about traditions here. How do you stand, in what order do you do things, and in what pose do you sit in the car after obtaining the qualifications for the ceremonial photo? Of course, he thinks, you can't disrespect local customs, but he wants to stick out his tongue. Or at least take a picture, not like all the other drivers.

The command to start the engines sounds, and the teams scatter from the thirty-three cars, climb over the double barriers, and enter the pit stop. Rrrrrrrrrrrrr. Rrrrr-rrrrrr. The parade lap. RRRDDddddzzzz. Several warm-up laps, slowly weaving, to heat the tires and improve grip on the track.

Green flag.

The engines explode.

The cars roar with a terrible rumble like intergalactic jet fighters tearing through the sound and light barrier. A little more, and they'll take off. Dzzzzzzz-ZZZZZZ.

The sound is as if hell suddenly fell on Indianapolis, and death bombers directly through your brain are about to blow everything to hell here, wipe off the face of the earth and everything in their path. The fierce roar of the stands is lost in this madness. Goosebumps on the skin, the cars spread out into a bright spot, leaving behind, like a comet, only a tail. Before you think, they're already here, making four kilometers in less than forty seconds. Vzzzzz. One. Vzzzz. Two. Vzzzzz. Three. The ninety-eighth in human history and the first in Aleshin's history, the "500 miles of Indianapolis" race began.

When race car driver Mikhail Aleshin finds himself behind the wheel of a racer, when he's finally alone, and there's no one around, only team communications in the earpiece, he feels this is exactly what he was born to do. Just him and the car, the sensation of which imprints on the subcortex of his brain. Thrill. Pilots who control these seven-hundred-kilogram monsters don't like to talk about what it's like. They say "ordinary" or "simple" people can't understand. An ordinary person would be very uncomfortable, says Aleshin. And how to explain it? How do you explain this feeling when a 2.2-liter engine with five to seven hundred horsepower roars behind you? It roars so close, as if you're flying, sitting on the Apocalypse rocket. How do you describe this sensation when the car feels your slightest maneuver as if it's an extension of you? How can you tell what it's like to be squeezed in a tight cockpit? Autopilots are like military test pilots: carriers of knowledge so sacred, a feeling so sweet and simultaneously shameful, they don't talk about it. They stand on a peak others can never climb. They are rock stars. And everyone below wants to know — what it's like.

Indescribable.

Sometimes, Aleshin, when meeting people who know nothing about him, introduces himself as a regular athlete or even a student to avoid all these questions. To avoid describing what's impossible to explain

Five belts securely fasten the driver's body to the seat. Vision narrows — only the track running by, as in a computer game, is in sight. Due to vibration, vision blurs, and eyes tire faster. Consciousness is at its limit; you can only concentrate on the path itself; everything else is blocked out and disappears. Around is the monotonous roar and signals from the radio. No smells; there's no time for that. It's like flying in a vacuum. When steering, it feels like a fifteen-kilogram weight is tied to your hands, which you must pull with each turn. Due to the G-forces in the turns, the lungs compress, and you can't breathe. You breathe before the turn, enter, hold your breath, exit, breathe again, and then another turn. The head must be held straight, and the neck must be specially trained because this vast helmet turns the head into a heavy pendulum. Special aerodynamic protrusions on the helmet protect the head from the fierce air stream, trying to lift the racer's head and tear off the helmet. The strain on the neck is comparable to driving a regular car with a twenty-kilo weight strapped to your head.

The racer is clothed in a base layer made of synthetic fire-resistant fiber. Under the helmet, a balaclava. Over the body — a dense fireproof suit, fire-resistant socks, and shoes. Races are usually held in warm weather, and in such a suit with a heated engine behind, the racer sweats profusely and loses a couple of liters of fluid. Dehydration leads to weight loss; sometimes, you can lose up to four kilograms per race. To cope with dehydration, pilots undergo special training, and helmets are equipped with a drinking water supply system. Vibrations, G-forces, heat, and warm gear lead to the racer's body temperature rising and sometimes reaching 39.4 degrees Celsius. And after the race — emptiness, as if there was never anything inside.

Thrill.

IndyCar cars are much larger than Formula 1 cars and accelerate better. Initially, Aleshin was shocked by such a machine. Unlike Formula 1, in IndyCar, racers have almost identical cars, and the settings are their own. But even more challenging are the new, unknown tracks, for which there is virtually no time to prepare appropriately. And the oval of the Motor Speedway is the most difficult. It seems, well, it's just an oval. But Aleshin immediately understood that it's a complex art. On the long straights of the oval, you can accelerate up to 400 kilometers per hour; there's room for maneuvers and actual combat. There are several trajectories; the car is heavily shaken on the upper ones and becomes unpredictable at slow speeds. Entering the pit lane, it can be thrown to the side in the most harmless situation. Thinking and acting have to be one and a half times faster, and the fight with the opponent can last several laps in a row, and it's impossible to keep track of everything. But what a pleasure Aleshin gets from understanding that he did almost everything perfectly and wasn't scared. During the qualifications, he flew at the limit, 380 kilometers per hour; the car nearly got torn off, but he didn't hit the brakes. Otherwise, he would have started not 15th but 25th. Is it adrenaline?

Oh no, it's something else entirely.

In the first lap, Aleshin immediately loses three positions, letting American Ryan Hunter-Reay, hereditary French racer Sebastien Bourdais, and Brazilian Tony Kanaan ahead. Ahead, James Hinchcliffe and Indianapolis racer Ed Carpenter exchange the first place. Aleshin breaks out to the sixteenth place. Over the roar of engines, the commentator's voice prevails. By the twenty-eighth lap, the first wave of pit stops begins.

The thirty-third lap. Mikhail Aleshin breaks ahead and, for a lap, becomes the race leader. What a feeling! He understands it's temporary, just a moment, that he needs a pit stop, but what an incredible feeling: not everyone managed to get here. The lap ends, the race continues, Aleshin pits, and the battle for the leading positions resumes. Hinchcliffe. Carpenter. Power. In lap 58, Marco Andretti overtakes power at the third turn and races first. Aleshin is in the eighteenth place. Helio Castroneves is first on lap 62, Scott Dixon on lap 64, he is replaced by former "Formula 1" racer Juan Pablo Montoya. The last time he led "Indy500" was in 2000. Aleshin is overtaken by another rookie, Sage Karam. The second wave of pit stops, Aleshin again waits, breaks through to the sixteenth position, and drives between Bourdais and Justin Wilson. Castroneves becomes the leader again, and Andretti and Carpenter besiege him. Rrrrrr. Rrrrr. Rrrrr. DZZZZZZ.

After the tenth lap, many spectators gradually descend from the stands and wander around the track premises. They buy hot dogs, try on souvenir baseball caps, and play beer pong: pickups, RVs, and enormous trucks for transporting teams and cars. Naked women dance on the lawn. Men are merry in cargo shorts and stretched tank tops. Women of all ages dressed like tequila vendors: short denim shorts, tank tops, and high leather boots. From the back, you can't tell how old they are. The hills are overgrown with tents, chairs, tables, and families. Right behind, the fighter jet cars roar. They're obvious, but everyone watches the race on the vast monitors everywhere: at least you can somewhat understand what's happening. Mounted police patrol, people play frisbee by the lake.

"Hey! Who's winning?" you ask the guy in those awful sunglasses and an "America" T-shirt.

"I'm rooting for Carpenter! He's a local!"

"And who's leading?"

"Dunno! We should head back to our seats; we've been drinking and all that shit. Carpenter's a local!"

The race has started, without any doubt. Everyone heard the beginning. But it seems it doesn't matter. It's just an excuse.

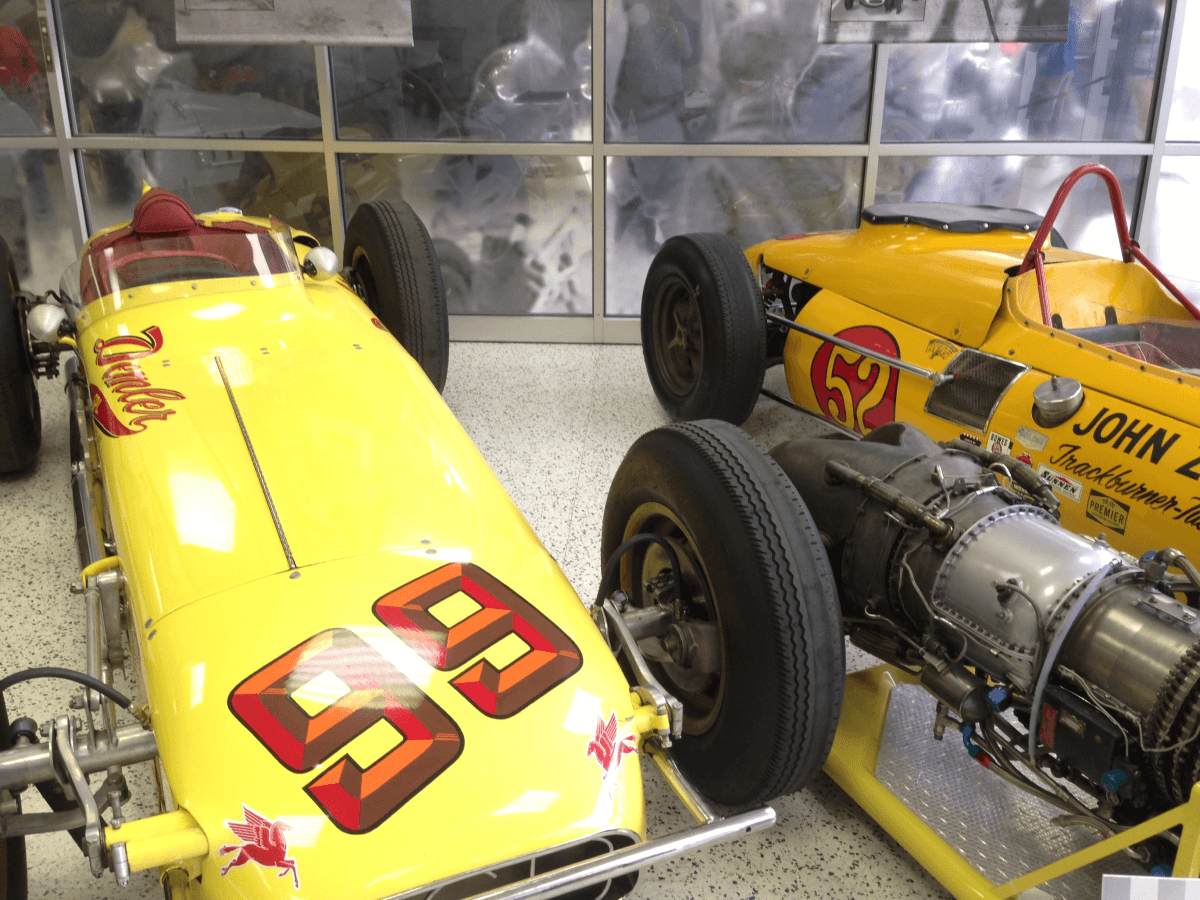

The Hall of Fame museum gathers an impressive collection of rare cars from the dawn of humanity. Flat, like frogs; square; two-seater; round; resembling rockets; smooth, like a woman's thigh. All operational, except for two cars — one was dismantled by its donors to prevent it from being driven in the museum, and the other burned during a demonstration run in honor of its centenary. A young tour guide excitedly explains the essence of the race:

"Being fifteenth or sixteenth is cool! When you're first, you burn fuel, and everyone's ready to kill for your place. That's crap. When you're in the middle, you can race, exchange places, and burst at the end. But the coolest is to be last, thirty-third. Why? Because everyone gets a prize money, and if you finish without wrecking the car, you get a check for two hundred eighty-nine thousand bucks, that's why," the guide smiles. Then he points to a huge photograph on the wall. There, a dirty man, smeared in shit, sits shirtless in a sink. "Yes, this photo shows a twentieth-century racer. He won, of course! He's pleased.

The cavalcade of leaders. Castroneves — Carpenter — Hunter-Reay — Dixon — Montoya. And so on. Rrrrr. Rrrr. Rrrr. Aleshin's car starts vibrating intensely. Dzzzzz. The vibration increases with each lap, and Aleshin sees the track worse and worse. Aleshin gets angry and drives on. The car's rear breaks away more often, and the wheels lose grip due to vibration. After four laps, Aleshin feels as if the left rear part of the car is lying flat. He pits earlier than scheduled, losing position. Mechanics deal with the technical issue for two minutes — a hub nut has come loose. Aleshin is now four laps behind the others. Damn it! Damn it! He swears over the radio. Usually, especially in front of girls, he doesn't swear, but he can't help it: to drive another hundred laps, and there's no chance of winning. And he hates it when something is out of his control.

He starts again. Gradually makes up laps. 29th. 28th. 27th. 26th. 25th. 24th. 23rd. 22nd. 21st. 21st. 21st.

On lap 150, Charlie Kimball's car, coming out of the second turn, suddenly spins and crashes left side into the wall. The impact spins the vehicle again. Lap 168, Dixon spins on the fourth turn and crashes heavily into the barrier and the wall. Dixon gets out of the car on his own. The crowd roars. Lap 176, Hinchcliffe and Carpenter finally collide with each other, crash into the barrier, and get out of the cars on their own. Lap 191, Townsend Bell crashes into the barrier with a bang. The race is stopped, red flag.

In the fifty-four years that John Reeves from his famed Tennessee whiskey state has been coming to these races, they've all finally blended in his gray head. Someone always arrives first, someone constantly barely crawls to the finish, someone crashes completely, burns, and dies, and someone will never sit behind the wheel again. Reeves owns a media company with the wise face of actor Morgan Freeman, a silver beard, and a white, shiny smile like a museum race car. In his expensive cream jacket, broad hat, and pink shirt squeezed by a bolo tie, he watches the last laps of the race and chuckles. His foot in a pointed boot on the frame of the media center window, towering over the roaring stand, his gaze quickly shifts from the track to the monitors and back. It hardly matters who wins, thinks Reeves. What difference does it make? The main thing is it's almost always a good race. Reeves knows there are many more races in the world and thousands of racers of all kinds, but only these thirty-three got the right to fly here, under the sun of Indiana; for this, they all got these cumbersome rings — they've already won at life.

The race resumes. The roar grows, and the crowd pauses momentarily on an exhale. Ryan Hunter-Reay's and Helio Castroneves's yellow cars are taken out for the final lap. John Reeves and the entire media center press against the glass. Hunter-Reay breaks from behind Castroneves. The fight is for every centimeter—the last turn. Castroneves tries to overtake Hunter-Reay but is six-hundredthsPower of a second late.

Checkered flag, explosion.

It's over.

The roar drowns out the jet engines; John Reeves looks tenderly at the track and stretches in his southern drawl:

"An American won Indianapolis!" — he raises his hands and immediately puts them back in his pockets. — "An American won Indy! It was a damn good race, I tell you, yes. A damn good race."

The stands empty quickly. Tables are gathered, and barbecues are rolled up. Pristine silence reigns instantly. A skinny guy with a backpack heads to the exit. Somehow, he squeezed through a two-meter fence to the crash site of Ed Carpenter and snagged a half-meter carbon fiber piece of the car. He stuffed it in his backpack like a frozen fish and walked calmly as if something resembling a shovel wasn't sticking out of his bag. Last time, he took the nose from Juan Pablo Montoya's crashed car. One day, he'll build his fighter and come to the race.

After the race, the pilots resemble the living dead. Juan Pablo Montoya hides from fans in the garage, sneaks away, gets on a motorcycle, and heads to the airport. Almost having taken first place, Helio Castroneves tries his best to appear cheerful and, seeing nothing in front of him, mechanically signs everything fans hand him. "Sign my shirt," whispers a beauty in his garage. — "And take it off me." But Helio doesn't even pay attention to her. Will Power is empty as after a Dementor's kiss: eyes focused on nowhere. Mikhail Aleshin returns to the garage, sets down his mud-covered helmet, and runs away from scheduled meetings.

In the evening after the race, at his rented apartment in downtown Indianapolis, Mikhail Aleshin will emerge from the shower and realize it's not all that bad. Yes, he wanted to show the Americans "Kuzkin's mother." He constantly encounters the words "What's so unique about these Russians?" he wants to show them precisely what: come, win their race, enter at least the top five, so they'd be afraid, so they'd know. Yes, he tried, he started 15th, but due to that damn nut, he finished 21st. Not a brilliant finish. And for him, there are no places other than the first. Everything else is unacceptable.

But everything is indeed not so wrong, thinks the cooled-down Aleshin: he managed to finish, made it, gained experience, and it never goes to waste. And this is just the beginning of a new long climb.

And the next day, during rides to interviews, events, and four invitation dinners, Aleshin won't even remember where his silver ring, a symbol of belonging to a closed caste, went from his ring finger. He took it off or rolled it somewhere in the car.

The race is over. But not for him.

1. Transform your identity crisis and own your story with an online narrative therapy session. Reduce anxiety and discover new perspectives through these collaborative conversations

2. Turn your life experience and passion into captivating media products with step-by-step coaching. I will guide you from ideation to creation, and together we'll craft your dream project

If you have any questions, feel free to reach me at most@hey.com